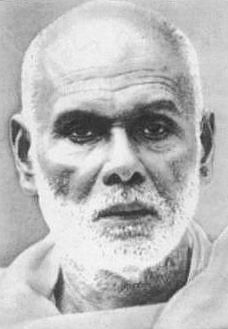

Kumaran Asan

Mahakavi Kumaran Asan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 12 April 1871 Kaayikkara Kadakkavoor, Chirayinkeezhu, Thiruvananthapuram, Travancore |

| Died | 16 January 1924 (aged 50) Alappuzha, Travancore, Kerala |

| Occupation | Poet and writer |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse | Bhanumathiamma |

| Children | Prabhakaran and Sudhakaran |

| Relatives |

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Reformation in Kerala |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Notable people |

|

| Others |

Mahakavi Kumaran Asan (12 April 1871 – 16 January 1924) was a poet of Malayalam literature, Indian social reformer and a philosopher. He is known to have initiated a revolution in Malayalam poetry during the first quarter of the 20th century, transforming it from the metaphysical to the lyrical and his poetry is characterised by its moral and spiritual content, poetic concentration and dramatic contextualisation. He is one of the triumvirate poets of Kerala and a disciple of Sree Narayana Guru. He was awarded the prefix "Mahakavi" in 1922 by the Madras university which means "great poet".[note 1]

Biography

[edit]

Asan[note 2] was born on 12 April 1873, in a merchant family belonging to Ezhava community in Kayikkara village, Chirayinkeezhu taluk, Anchuthengu Grama Panchaayath in Travancore[note 3] to Narayanan Perungudi, a polyglot well versed in Malayalam and Tamil languages, and Kochupennu as the second of their nine children.[1] His early schooling was at a local school by a teacher by name, Udayankuzhi Kochuraman Vaidyar, who taught him elementary Sanskrit after which he continued his studies at the government school in Kayikkara until he was thirteen. Subsequently, he joined the school as a teacher in 1889 but had to quit as he was not old enough to hold a government job. It was during this time, he studied the verses and plays of Sanskrit literature. Later, he started working as an accountant at a local wholesale grocer in 1890, the same year he met Shree Narayana Guru and became the spiritual leader's disciple.[2]

Narayana Guru's influence led Asan to spiritual pursuits and he spent some time at a local temple, in prayers and teaching Sanskrit.[1] Soon, he joined Guru at his Aruvippuram hermitage where he was known as Chinnaswami ("young ascetic"). In 1895, he moved to Bangalore and studied for law, staying with Padmanabhan Palpu. He stayed there only until 1898 as Palpu went to England and a plague epidemic spread over Bangalore and Asan spent the next few months in Madras before proceeding to Calcutta to continue his Sanskrit studies.[2] At Calcutta, he studied at Tarka sastra at the Central Hindu College, studying English simultaneously and also got involved with the Indian Renaissance, but his stay was again cut short due to plague epidemic.[3][4] He returned to Aruvippuram in 1900.[2]

Asan was also involved with the activities of the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam (SNDP) and became its secretary in 1904.[5] The same year, he founded Vivekodayam, a literary journal in Malayalam, and assumed its editorship.[6][7] Under his leadership, the magazine became a monthly from a bi-monthly.[8] In 1913, he was elected to the Sree Moolam Popular Assembly (Sri Moolam Praja Sabha),[2] the first popularly elected legislature in the history of India.[9] He relinquished the position at SNDP in 1919 and a year later, took over the editorship of Pratibha, another literary magazine In 1921, he started a clay tile factory, Union Tile Works, in Aluva but when it was found that the factory was polluting the nearby palace pond, he shifted the project to a site near Aluva river and handed over the land to SNDP for building an Advaitashramam.[10] Later, he moved to Thonnakkal, a village in the periphery of Thiruvananthapuram, where he settled with his wife.[2] In 1923, he contested in assembly election from Quilon constituency but lost to Sankara Menon.[11]

Asan married Bhanumathiamma, the daughter of Thachakudy Kumaran Writer in 1917.[12]

Death

[edit]Asan died on 16 January 1924, after a boat named Redeemer carrying him capsized in the Pallana river in Alappuzha.[13] His body was recovered after two days and the place where his mortal remains were cremated is known as Kumarakodi.[14]

Legacy

[edit]Remove the bonds of your effete tradition / Or it will ruin you within your own selves, Excerpts from Duravastha - Kumaran Asan[4]

Kumaran Asan was one of the triumvirate poets of modern Malayalam, along with Vallathol Narayana Menon and Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer.[15] Some of the earlier works of the poet were Subramanya Sathakam and Sankara Sathakam, which were devotional in content but his later poems were marked by social commentary.[16] He published Veena Poovu (the fallen flower) in December 1907 in Mithavadi of Moorkoth Kumaran which went on to become a literary classic in Malayalam; its centenary was celebrated in 2017 when a book, Veenapoovinu 100 was published which carried an introduction by M. M. Basheer and an English translation of the poem by K. Jayakumar.[17] Prarodanam, an elegy, mourning the death of his contemporary, friend and grammarian, A. R. Raja Raja Varma, Khanda Kavyas (poems) such as Nalini, Leela, Karuna, Chandaalabhikshuki, Chinthaavishtayaaya Seetha, and Duravastha are some of his other major works.[18] Besides, he wrote two epics, Buddha Charitha in 5 volumes and Balaramayanam, a three-volume work.[19]

Honours

[edit]In 1958, when Joseph Mundassery was the Minister of Education, the Government of Kerala acquired Asan's house in Thonnakkal and established the Kumaran Asan National Institute of Culture (Kanic), as a memorial for the poet,[20] the first instance in Kerala history when the government took over a poet's property to convert it into a memorial.[21] It houses an archives, a museum and a publications division. Asan Memorial Association, a Chennai-based organization, has built a memorial at Kayikkara, the birthplace of the poet.[22] They have also instituted an annual award, Asan Smaraka Kavitha Puraskaram, for recognising excellence in Malayalam poetry.[23] The award carries a cash prize of ₹30,000 and Sugathakumari, O. N. V. Kurup, K. Ayyappa Panicker and K. Satchidanandan are some of the recipients of the award.[24] Asan Memorial Senior Secondary School is a CBSE affiliated higher secondary school run by Asan Memorial Association.[25] The India Post issued a commemorative postage stamp depicting Asan's portrait in 1973, in connection with his birth centenary.[26][27][note 4]

Works

[edit]

Major works

[edit]| Year | Work | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1907 | Veena Poovu (The Fallen Flower)[28] | Asan scripted this epoch-making poem in 1907 during his sojourn in Jain Medu, Palakkad.[29] A highly philosophical poem, 'Veena Poovu' is an allegory of the transience of the mortal world, which is depicted through the description of the varied stages in the life of a flower. Asan describes in such detail about its probable past and the position it held. It is an intense sarcasm on people on high powers/positions finally losing all those. The first word Ha, and the last word Kashtam of the entire poem is often considered as a symbolism of him calling the world outside Ha! kashtam (How pitiful).[30] |

| 1911 | Nalini[31][32] | It is a love poem, which details the love between Nalini and Diwakharan.[33] |

| 1914 | Leela[34] | A deep love story in which Leela leaves Madanan, her lover and returns to find him in forest in a pathetic condition. She thus realises the fundamental fact Mamsanibhadamalla ragam (true love is not carnal)[35] |

| 1919 | Prarodanam (Lamentation)[36] | An elegy on the death of A. R. Rajaraja Varma, a poet, critic and scholar; similar to Percy Bysshe Shelley's Adonaïs, with a distinctly Indian philosophical attitude.[6] |

| 1919 | Chinthavishtayaaya Sita (Reflective Sita) [37] | An exploration of womanhood and sorrow, based on the plight of Sita of Ramayana.[38] |

| 1922 | Duravastha (The Tragic Plight)[39] | A love story depicting the relationship between Savithri, a Namboothiri heiress and Chathan, a youth from a lower caste. A political commentary on 19th and early 20th century Kerala.[40] |

| 1922 | Chandaalabhikshuki[41] | This poem, divided into four parts and consisting of couplets, describes an untouchable beggar-woman" (also the name of the poem) who approaches Lord Ananda near Sravasti.[42] |

| 1923 | Karuna (compassion)[43] | The story of Vasavadatta, a devadasi, and Upagupta, a Buddhist monk.[44][45] Tells the story of sensory attraction and its aftermath.[46] |

Other works

[edit]

| Year | Work | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | Sthothrakrithikal | Poetry anthology |

| 1901 | Saundaryalahari | Poetry anthology |

| 1915–29 | Sree Budhacharitham[47] | This is an epic poem comprising 5 volumes (perhaps Kumaran Asan's longest work), written in couplets |

| 1917–21 | Baalaraamaayanam | This is a shorter epic poem consisting of 267 verses in three volumes. Most of these verses are couplets, with the exception of the last three quatrains viz. Balakandam (1917), Ayodhyakandam (1920) and Ayodhyakandam (1921). There are, therefore, 540 lines in all |

| 1918 | Graamavrikshattile Kuyil[48] | |

| 1922 | Pushpavaadi[49] | |

| 1924 | Manimaala[50] | Poetry anthology |

| 1925 | Vanamaala[51] | Poetry anthology |

Kumaran Asan also wrote many other poems. Some of these poems are listed in the book Asante Padyakrthikal under the name "Mattu Krthikal" (Other Works):

- Sadaachaarasathakam

- Sariyaaya Parishkaranam

- Bhaashaaposhinisabhayodu

- Saamaanyadharmangal

- Subrahmanyapanchakam

- Mrthyanjayam

- Pravaasakaalaththu Naattile Ormakal

- This is another collection of poems that come from various letters Kumaran Asan wrote over the course of several years. None of the poems were longer than thirty-two lines.

- Koottu Kavitha

The other poems are lesser known. Only a few of them have names:

- Kavikalkkupadesam

- Mangalam

- Oru Kathth

- This is another one of Asan's letter-poems.

- Randu Aasamsaapadyangal

poems or stories which are written by kritikal 1. Leela 2. veenpuv 3. nlene 4. kruna 4. parodnam

Prose

[edit]- Kumaran Asan, N. (1991). Brahmasri Sri Narayana Guruvinte Jeevacharithra Samgraham (3rd. ed.). Thonnakkal: Kumaran Asan Memorial Committee.

- Kumaran Asasn, N. ed (1984). Kumaran Asante Gadyalekhanangal v.1. Thonnakkal, Trivandrum: Kumaran Asan Memorial Committee.

3 volumes

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Kumaranasan; Shaji, S. (2010). Aasante kathukal. Kottayam: Sahitya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society.

Translations

[edit]- Asan, Kumaran; Gangadharan, P. C (1978). The Tragic plight (1st ed.). Thonnakkal : Kumaran Asan Memorial Committee; [Madras : distributed by Macmillan].

Works on Asan

[edit]- E. K. Purushothaman, ed. (2002). Suryathejas — Studies on Asan Poetry. Asan Memorial Association.

- M. Govindan, ed. (1974). Poetry and Renaissance: Kumaran Asan birth centenary volume. Madras: Sameeksha.

- Pavitran P. (1994). Evolution of the poetic life of Kumaran Asan: A psychu-philosiphical enquiry.

- Nithyachaithanya Yathi (1994). Kumaranasan. Author.

- Kumaran, Murkoth; Madhavan K. G (1966). Asan vimarsanathinte aadya rasmikal. Kottayam: Vidhyarthimithram.

- Sreenivasan, K. (1981). Kumaran Asan: Profile of a poets vision. Thiruvananthapuram: Jayasree Pubs.

- George, K. M. (1972). Kumaran Asan. New Delhi: Sahitya Academi.

- Sukumar Azhikode. Asante Seethakavyam. Lipi Publications. ISBN 978-81-88011-74-2.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Asan was commonly referred to as Mahakavi Kumaran Asan (the prefix Mahakavi, awarded by Madras University in 1922, means "great poet" and the suffix Asan means "scholar" or "teacher")

- ^ Asan was commonly referred to as Mahakavi Kumaran Asan (the prefix Mahakavi, awarded by Madras University in 1922, means "great poet" and the suffix Asan means "scholar" or "teacher")

- ^ present-day Thiruvananthapuram district of Kerala, South India

- ^ Please check year 1973

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Biography on Kerala Sahitya Akademi portal". Kerala Sahitya Akademi portal. 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Chronicle". kanic.kerala.gov.in. 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ Das, Sisir Kumar, ed. (2006). "The Narratives of Suffering: Caste and the Underprivileged". A History of Indian Literature 1911–1956: Struggle for Freedom: Triumph and Tragedy (Reprinted ed.). Sahitya Akademi. pp. 306–308. ISBN 978-81-7201-798-9.

- ^ a b Natarajan, Nalini (1996). Handbook of Twentieth-Century Literatures of India. Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. pp. 183–185. ISBN 0-313-28778-3. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "SNDP Yogam". Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ a b Sisir Kumar Das (2005). History of Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 257–. ISBN 978-81-7201-006-5.

- ^ S. N. Sadasivan (2000). A Social History of India. APH Publishing. pp. 600–. ISBN 978-81-7648-170-0.

- ^ "Kumaranasan - Kerala Media Academy". archive.keralamediaacademy.org. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "History of legislative bodies in Kerala-- Sri Moolam Praja Sabha". keralaassembly.org. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Kumaran Asan As A Business Man". veethi.com. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Kumaran Aasan once contested from Kollam". Manorama. 20 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ K. M. George (1972). Makers of Indian Literature. Kumaran Asan. Sahitya Akademi. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Kumaranasan Biography Kerala PSC". pscteacher.com. 3 March 2019. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Kumarakodi - District Alappuzha". Government of Kerala. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "When poesy met poise on stage - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Kumaran Asan - Indian poet". Encyclopedia Britannica. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Veena Poovu: still in bloom". The Hindu. 21 December 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Kumaran Asan - A Biography" (PDF). sayahna.org. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Books and Works". kanic.kerala.gov.in. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Kumaran Asan National Institute of Culture". kanic.kerala.gov.in. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "The Memorial of Asan". www.keralaculture.org. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Asan Memorial, Kayikkara". www.keralaculture.org. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Asan Smaraka Kavitha Puraskaram". asaneducation.com. 3 March 2019. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "List of Awardees". asaneducation.com. 3 March 2019. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "ASAN Memorial Senior Secondary School". asancbse.com. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Amrut Philately Gallery - 1973". amrutphilately.com. 3 March 2019. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Commemorative and definitive stamps". postagestamps.gov.in. 3 March 2019. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Kumaran Asan, N. (2007). Veenapoovu. Kottayam: D C Books. ISBN 9788126417995.

- ^ Paul, G.S. (21 December 2007). "The Hindu : Friday Review Thiruvananthapuram / Dance : Visual poetry". Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ Mohan Lal (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 4529–. ISBN 978-81-260-1221-3.

- ^ Kumaran Asan (January 2009). Nalini : Patam, Patanam, Vyakhyanam. DC Books. ISBN 9788126424108. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Kumaran Asan (1970). Nalini. Thonnakkal: Sarada book dipo. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ K. M. George (1972). Western Influence on Malayalam Language and Literature. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-81-260-0413-3.

- ^ Kumaran Asan (1970). Leela. Thonnakkal: Sarada book dipo. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "ലീലയ്ക്ക് 100 വയസ്". Azhimukham (in Malayalam). 7 October 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Kumaran Asan (1968). Prarodanam. Thonnakkal: Sarada book dipo. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Kumaran Asan (1970). Chindavishtayaya Seetha. Thonnakkal: Sarada book dipo. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ George Pati (18 February 2019). Religious Devotion and the Poetics of Reform: Love and Liberation in Malayalam Poetry. Taylor & Francis. pp. 93–. ISBN 978-1-351-10359-6.

- ^ Kumaran Asan (1969). Duravastha. Sarada book dipo: Sarada book dipo. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Theatrical adaptation brings Kumaran Asan's poem to life - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Kumaran Asan (1970). Chandala bhikshuki. Thonnakkal: Sarada book dipo. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ S. N. Sadasivan (2000). A Social History of India. APH Publishing. pp. 634–. ISBN 978-81-7648-170-0.

- ^ Kumaran Asan (1969). Karuna. Sarada book dipo: Sarada book dipo. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ S. N. Sadasivan (2000). A Social History of India. APH Publishing. pp. 681–. ISBN 978-81-7648-170-0.

- ^ P. P. Raveendran (2002). Joseph Mundasseri. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-81-260-1535-1.

- ^ Elleke Boehmer; Professor of World Literature in English Elleke Boehmer; Rosinka Chaudhuri (4 October 2010). The Indian Postcolonial: A Critical Reader. Routledge. pp. 228–. ISBN 978-1-136-81957-5.

- ^ Kumaran Asan, N. (1915). Sree Budhacharitham. Trivandram: Sarada Book Depot.

5 volumes

- ^ Kumaran Asan (1970). Kuyil. Sarada book dipo: Sarada book dipo. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Kumaran Asan (1969). Pushpavadi. Sarada book dipo: Sarada book dipo. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Kumaran Asan (1965). Manimala. Sarada book dipo: Sarada book dipo. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Kumaran Asan (1925). Vanamala. Sarada book dipo: Sarada book dipo. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

External links

[edit]- "Portrait commissioned by Kerala Sahitya Akademi". Kerala Sahitya Akademi. 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- YesLearners Kerala (18 April 2017). "Kumaranasan - (കുമാരനാശാന്) - Kerala Renaissance". YouTube. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Audiopedia (26 August 2014). "Kumaran Asan - A Lecture". YouTube. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- binbrainvideos (5 April 2010). "Kumaran Asan's tomb at Alappuzha". YouTube. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- 1873 births

- 1924 deaths

- Indian male poets

- Malayalam poets

- Poets from Kerala

- Activists from Kerala

- Indian Sanskrit scholars

- Writers from Thiruvananthapuram

- The Sanskrit College and University alumni

- University of Calcutta alumni

- Deaths by drowning in India

- Deaths due to shipwreck

- Indian social reformers

- 20th-century Indian poets

- 19th-century Indian poets

- 19th-century Indian male writers

- Scholars from Thiruvananthapuram

- 20th-century Indian male writers

- Poets from British India