Destination Moon (film)

| Destination Moon | |

|---|---|

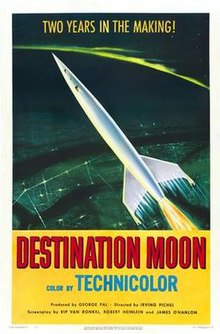

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Irving Pichel |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Produced by | George Pal Walter Lantz (uncredited) |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Lionel Lindon |

| Edited by | Duke Goldstone |

| Music by | Leith Stevens |

| Animation by | Walter Lantz |

| Color process | Technicolor |

Production companies | George Pal Productions Walter Lantz Productions |

| Distributed by | Eagle-Lion Classics |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $592,000[1] |

| Box office | $5 million[2] or $1.3 million (US)[3][4] |

Destination Moon (a.k.a. Operation Moon) is a 1950 American Technicolor science fiction film, independently produced by George Pal and directed by Irving Pichel, that stars John Archer, Warner Anderson, Tom Powers, and Dick Wesson. The film was distributed in the United States and the United Kingdom by Eagle-Lion Classics.

Destination Moon was the first major U.S. science fiction film to deal with the practical scientific and engineering challenges of space travel and to speculate on what a crewed expedition to the Moon would look like. Noted science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein contributed to the screenplay.

The film's premise is that private industry will mobilize, finance, and manufacture the first spacecraft to the Moon, and that the U.S. government will be forced to purchase or lease the technology to remain the dominant power in space. Different industrialists cooperate to support the private venture.

In the final scene, as the crew approaches the Earth, the traditional "The End" title card heralds the dawn of the coming Space Age: "This is THE END...of the Beginning".[5][page needed]

Plot

[edit]When their latest rocket test fails and government funding collapses, rocket scientist Dr. Charles Cargraves and space enthusiast General Thayer enlist the aid of aircraft magnate Jim Barnes. With the necessary millions raised privately from a group of patriotic U.S. industrialists, Cargraves, Thayer, and Barnes build an advanced single-stage-to-orbit atomic powered spaceship, named Luna, at their desert manufacturing and launch facility.

The project is soon threatened by a ginned-up public uproar over "radiation safety" but the three circumvent legal efforts to stop their expedition by launching the world's first Moon mission ahead of schedule. As a result, they must quickly substitute Joe Sweeney as their expedition's radar and radio operator, a replacement for Brown, now in the hospital with appendicitis.

En route to the Moon they are forced to spacewalk outside. They stay firmly attached to Luna with their magnetic boots so they can easily walk up to and free the frozen piloting radar antenna that the inexperienced Sweeney innocently greased before launch. In the process, Cargraves becomes untethered in free fall and is lost overboard. He is retrieved by Barnes, who cleverly uses a large oxygen cylinder with nozzle, retrieved by General Thayer, as an improvised propulsion unit to return them to Luna.

After achieving lunar orbit, the crew begins the complex landing procedure, but expedition leader Barnes uses too much fuel during the descent. Safely on the Moon, they explore the lunar surface and describe by radio their view of the Earth, as contrasted against the star-filled lunar night sky. Using forced perspective, Barnes photographs Sweeney pretending to "hold up" the Earth like a modern Atlas. Events take a serious turn for the crew, however, when they realize that with their limited remaining fuel they must lighten Luna in order to achieve lunar escape velocity.

No matter how much non-critical equipment they strip and discard on the lunar surface, the hard numbers radioed from Earth continue to point to one conclusion: one of them will have to remain on the Moon if the others are to safely return to Earth. With time running out for their return launch window, the crew continues to engineer their way home. They finally jettison the ship's radio, losing contact with Earth. In addition, a spent oxygen cylinder is used as a tethered, suspended weight to pull their sole remaining space suit outside through the open airlock, which is then remotely closed and resealed. With the critical take-off weight finally achieved, and with all her crew safely aboard, Luna blasts off from the Moon for home.

Cast

[edit]- John Archer as Jim Barnes

- Warner Anderson as Dr. Charles Cargraves

- Tom Powers as General Thayer

- Dick Wesson as Joe Sweeney

- Erin O'Brien-Moore as Emily Cargraves

- Franklyn Farnum as Factory Worker (uncredited)

- Everett Glass as Mr. La Porte (uncredited)

- Knox Manning as Knox Manning (uncredited)

- Kenner G. Kemp as Businessman at meeting (uncredited)

- Mike Miller as Man (uncredited)

- Irving Pichel as Narrator of Woody Woodpecker Cartoon (uncredited)

- Cosmo Sardo as Businessman at Meeting (uncredited)

- Bert Stevens as Businessman at meeting (uncredited)

- Ted Warde as Brown (uncredited)

- Grace Stafford as Woody Woodpecker (voice) (uncredited)

- Mel Blanc as Woody Woodpecker's trademark laugh (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Before Destination Moon, there were very few serious science fiction films: 1929's Frau im Mond (English Woman in the Moon), 1931's Frankenstein, and 1936's Things to Come are antecedents (though containing fantasy elements). However, the more juvenile-oriented Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers stories of the 1930s syndicated science fiction newspaper comic strips that were both adapted into radio serials and Universal Pictures film serials.

George Pal was a Hungarian who made commercials that played as short subjects with feature films in Europe. He later advanced into animated cartoon-like short features that were made using carefully hand-manipulated tiny sculptures instead of drawings; these shorts were called “Puppetoons”, and they became popular in Europe. Pal was in the U.S. when Hitler invaded Poland. He was offered a contract to produce his Puppetoons for Paramount Pictures, some of which were later nominated for Academy Awards.[6][7]

Development

[edit]By 1949, Pal wanted to get into feature film production. He convinced the independent Eagle-Lion Films to co-finance his own two-picture deal, with him putting up half of the money. Part of the finance came from Peter Rathvorn and Floyd Odlum, who used to run RKO.[8] The first of the two films, The Great Rupert, about a Puppetoon-like dancing squirrel, starring popular comic Jimmy Durante, flopped at the box office. But his second feature, Destination Moon, was a major hit.

Eagle-Lion's publicity department saw the promotional possibilities for a film about a rocket expedition to the Moon. They promoted the film heavily in both general family magazines and in many science fiction digest magazines, emphasizing its Technicolor visuals and expert consultants. Destination Moon was constantly in the limelight of the era's popular press, including the high-profile Life magazine; by the time the film was shown in theaters, its success seemed a foregone conclusion.[9]

Pal commissioned an initial screenplay from screenwriters James O'Hanlon and Rip Van Ronkel, but science fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein contributed significantly to Destination Moon's final screenplay, and also served as the film's technical adviser. Certain story elements from Heinlein's 1947 juvenile novel Rocket Ship Galileo were adapted for use in the film, and in September, 1950, he published a tie-in novella, "Destination Moon", based on the screenplay. The film's storyline also resembles portions of Heinlein's novel The Man Who Sold the Moon, which he wrote in 1949 but did not publish until 1951, a year after the Pal film opened.[5][page needed]

Matte paintings by Bonestell

[edit]Destination Moon uses matte paintings by noted astronomical artist Chesley Bonestell. These were used for the departure of the Luna from Earth; its approach to the Moon; the spaceship's landing on the lunar surface; and a panorama of the lunar landscape.[10] An oft-noted criticism of the film is the fact that the lunar surface is crisscrossed with gaping cracks. Mudcracks would imply that the surface was once mud, which requires water, and the Moon does not have water. Bonestell, who painted the large backdrop that mimicked lunar crags and mountains, was unhappy with the cracks, which were designed by art director Ernst Fegté. “That was a mistake”, he insisted to Gail Morgan Hickman, author of The Films of George Pal. But Pal explained to Hickman, “Chesley was right, of course ... but we were shooting on a small sound stage because of our limited budget. We had to make the set look bigger. Chesley designed a beautiful backdrop, but it needed something to give it depth. That’s why we made the cracks. The cracks in the foreground were big and those in the distance were small, so it gave a real feeling of perspective. For some scenes we even used midgets in small spacesuits to add to the feeling of depth”.[6][7][11]

Director

[edit]Irving Pichel began his Hollywood career as an actor during the 1920s and early 1930s, in such films as Dracula's Daughter and The Story of Temple Drake.[12] He began directing in 1932; Destination Moon was his 30th film. Pichel was blacklisted after he was subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947, despite having never been called to testify.[13] He directed five more films after Destination Moon before his death in 1954.[14]

Woody Woodpecker

[edit]George Pal and Walter Lantz, who created the cartoon character Woody Woodpecker, had been close friends ever since Pal left Europe and arrived in Hollywood. Out of friendship and for good luck, Pal always tried to include Woody in all his films. (On the commentary track of the Special Collector's DVD Edition of George Pal's science fiction film The War of the Worlds (1953), actors Ann Robinson and Gene Barry point out that Woody can be seen in a tree top, center screen, near the beginning of their film.)

Pal incorporates Woody (voiced by Grace Stafford) in a cartoon shown within the film that explains, in layman's terms to a 1950 movie theater audience, the scientific principles behind space travel and how a trip to the Moon might be accomplished.[15] The cartoon is shown to a gathering of U.S. industrialists who, it is hoped, will patriotically finance such a daring venture before an unnamed, non-western power can do so successfully.[16]

Production credits

[edit]- Director — Irving Pichel

- Producer — George Pal

- Writing — Rip Van Ronkel, Robert A. Heinlein, and James O'Hanlon (screenplay), Robert A. Heinlein (underlying novel)

- Cinematography — Lionel Lindon (photography)

- Art direction — Ernst Fegté (production designer), George Sawley (set decoration)

- Film editor — Duke Goldstone

- Production supervisor — Martin Eisenberg

- Cartoon sequences — Walter Lantz

- Technicolor color consultant — Robert Brower

- Assistant director — Harold Godsoe

- Special effects — Lee Zavitz

- Makeup artist — Webster Phillips

- Sound — William Lynch

- Music — Leith Stevens (music), David Torbett (orchestration)

- Technical — Chesley Bonestell (technical advisor of astronomical art), Robert A. Heinlein (technical advisor), John S. Abbott (technical supervisor)

Soundtrack

[edit]The soundtrack music, written by composer Leith Stevens, is noteworthy for its atmospheric themes and musical motifs, all of which add subtle but important detail and emotion to the various dramatic moments in the film. According to George Pal biographer Gail Morgan Hickman, "Stevens ... consulted with numerous scientists, including Wernher von Braun, to get an idea of what space was like in order to create it musically."[6][17][7] The Stevens Destination Moon film score had its first U.S. release in 1950 on a 10-inch 33 rpm Monaural LP by Columbia Records (#CL 6151):[18]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Earth: Prelude" | Leith Stevens | 02:50 |

| 2. | "Earth: Planning and Building of the Great Rocket" | Stevens | 05:03 |

| 3. | "In Outer Space" | Stevens | 06:53 |

| Total length: | 14:46 | ||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "On the Surface of the Moon: The Crater Harpalus" | Stevens | 04:10 |

| 2. | "On the Surface of the Moon: Exploring the Moon" | Stevens | 01:58 |

| 3. | "On the Surface of the Moon: The Dilemma" | Stevens | 02:40 |

| 4. | "On the Surface of the Moon: Escape from the Moon and Finale" | Stevens | 03:11 |

| Total length: | 11:59 | ||

Later in the 1950s, the score was re-released on a 12-inch high-fidelity mono LP by Omega Disk (#1003). Omega Disk re-released it in 1960 as a stereophonic 33 1/3 LP (#OLS-3). In 1980, the score was re-released on stereo LP by Varèse Sarabande (#STV 81130) and again in 1995 on stereo LP by Citadel Records (#STC 77101). An expanded and complete 56.32 minute version of Steven's original film score, limited to 1,000 copies, was released on CD in 2012 by Monstrous Movie Music (#MMM-1967); also on the CD is Clarence Wheeler's incidental music used for the film's Woody Woodpecker cartoon. An illustrated 20-page booklet of liner notes is also included.[19]

Reception

[edit]Release

[edit]Despite a budget of approximately $500,000 and a large national print media and radio publicity campaign preceding its delayed release, Destination Moon ultimately became the "second" space adventure film of the post-World War II era. Piggybacking on the growing publicity and expectation surrounding the Pal film, Lippert Pictures quickly shot Rocketship X-M in 18 days on a $94,000 budget. The film, about the first spaceship to land on Mars, opened theatrically 25 days before the Pal feature.[5][page needed] Nevertheless, despite the fact that Destination Moon was indeed the second space film of the era to be released to theaters, its two years of production, hefty budget, its use of Technicolor, its significant influence in the film industry, and the technical consultation by important scientists and engineers during production—the ultimate value of the picture, also its priority, transcends the mere physical fact that it was second in the marketplace. Certainly, Rocketship X-M itself would never have been made if the highly probable success of Destination Moon had not caught Robert Lippert's attention.[7]

Critical reaction

[edit]The film has had numerous admirers and detractors over the years.

Contemporary reviews

[edit]Bosley Crowther in his review of Destination Moon for The New York Times, opined, "... we've got to say this for Mr. Pal and his film: they make a lunar expedition a most intriguing and picturesque event. Even the solemn preparations for this unique exploratory trip, though the lesser phase of the adventure, are profoundly impressive to observe".[20]

Science writer, science fiction novelist, and early space enthusiast Arthur C. Clarke wrote: "[T]his [is a] remarkable exciting and often very beautiful film, the first Technicolor expedition into space. After years of comic strip treatment of interplanetary travel, Hollywood has at last made a serious and scientifically accurate film on the subject, with full cooperation of astronomers and rocket experts. The result is worthy of the enormous pains that have obviously been taken, and it is a tribute to the equally obvious enthusiasm of those responsible".[21]

Later 20th century reviews

[edit]“Trivial in plot ... viewed today Destination Moon is less than impressive; the rocket journey is ploddingly consistent with the scientific standards of 1950... Destination Moon makes rather dull viewing nowadays”. —John Baxter in Science Fiction in the Cinema (1970)[22]

In his 1979 autobiography, science writer and science fiction novelist Isaac Asimov called the Pal film "the first intelligent science-fiction movie made".[23]

"Today it seems dated and slow-moving with flat characters". —John Brosnan in The Science Fiction Encyclopedia (1979)[24]

Peter Nicholls in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (1993) said, “Destination Moon is a film with considerable dignity and, in a quiet way, a genuine sense of wonder”.[25]

“The Destination Moon script seems colorless and wooden”. —Phil Hardy in The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Science Fiction (1994)[26]

21st century reviews

[edit]“Destination Moon now seems tame”. —John Stanley in Creature Features: The Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Movie Guide (2000)[27]

“The visual effects in Pal’s [Destination Moon] were art. They are aesthetically stunning ... they bear the imprint of gifted artists’ hands.... The Luna rocket of Destination Moon still [has] the capacity to astonish”. —Justin Humphreys in “A Cinema of Miracles: Remembering George Pal”, from the memorial program notes for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ George Pal: Discovering the Fantastic: A Centennial Celebration, August 27, 2008[28]

In 2010, author and film critic Leonard Maltin awarded the film two-and-a-half out of four stars, calling it "modestly mounted but still effective". He also praised Bonestell's lunar paintings as being visually striking.[29]

“Destination Moon has aged badly ... [it] seems old hat and pedestrian to today’s viewers... But make no mistake about it, this picture, flaws and all, is a very important step in the evolution of the serious, special effects-laden science fiction motion picture that reached its peak with ... 2001: A Space Odyssey”. — Barry Atkinson in Atomic Age Cinema (2014)[30]

Awards and honors

[edit]Destination Moon won the Academy Award for Best Special Effects in the name of the effects director, Lee Zavitz. The film was also nominated for the Art Direction Academy Award, by Ernst Fegté and George Sawley.[31]

At the 1st Berlin International Film Festival it won the Bronze Berlin Bear Award, for "Thrillers and Adventure Films".[32]

Retro Hugo Awards: A special 1951 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation was retroactively awarded to Destination Moon by the 59th World Science Fiction Convention (2001) exactly 50 years later for being one of the science fiction films eligible in calendar year 1950.[33] (50 years, 75 years, or 100 years govern the time periods when a Retro Hugo can be awarded by a Worldcon for the years prior to 1953 when the Hugos were established and first awarded.)[34]

Adaptations

[edit]

Episode 12 of the Dimension X radio series was called Destination Moon and was based on Heinlein's final draft of the film's shooting script. During the broadcast on June 24, 1950, the program was interrupted by a news bulletin announcing that North Korea had declared war on South Korea, marking the beginning of the Korean War.[35]

Robert A. Heinlein published a short story adaptation of his screenplay in the September 1950 issue of Short Stories magazine.[36]

A highly condensed version of the Dimension X Destination Moon radio play was adapted by Charles Palmer and was released by Capitol Records for children, who had become familiar with their recordings through a Bozo the Clown-approved record series. The series featured 7-inch, 78-rpm recordings and full-color booklets which children could follow as they listened to the stories. The Destination Moon record was narrated by Tom Reddy, and Billy May composed the incidental and background music. The record's storyline took considerable liberties with the film's plot and characters, although the general shape of the film story remained.[37]

In 1950, Fawcett Publications released a 10-cent Destination Moon film tie-in comic book.[38][39] DC Comics also published a comic book preview on the Pal film; it was the cover feature of DC's brand new science fiction anthology comic book Strange Adventures # 1 (September 1950).[5][page needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (8 June 1970). "Patience Key to Pal Success". Los Angeles Times. p. e19.

- ^ "Destination Moon (1950)". The Numbers. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ^ "Top Grosses of 1950". Variety. January 3, 1951. p. 58.

- ^ "8 War Pix Among Top 50 Grossers". Variety. 3 January 1951. p. 59.

- ^ a b c d Warren 2009.

- ^ a b c Hickman, Gail Morgan. The Films of George Pal. New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1977. ISBN 0-498-01960-8.

- ^ a b c d Miller, Thomas Kent. Mars in the Movies: A History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2016. ISBN 978-0-7864-9914-4.

- ^ HOLLYWOOD 'ANGELS': Rathvon and Odlum Ready to Finance Independent Producers -- Other Items By THOMAS F. BRADY HOLLYWOOD. New York Times 24 July 1949: X3.

- ^ Enter Robert L. Lippert, a producer of very inexpensive, very quickly made films designed to lure droves of the unwary into theaters. He noticed all this nationwide publicity for Destination Moon and decided to take advantage of all this free promotion for Destination Moon. While Destination Moon had been in production for two years and was costing more than half a million dollars, Lippert was able to quickly combine two rejected plots pitched earlier and separately by Kurt Neumann and Jack Rabin to create a similar film, Rocketship X-M, with $94,000 and a shooting schedule of 18 days. In fact, he made it so fast, it arrived in theaters a month before Destination Moon. Both films were hugely popular and financial successes, leading to the science fiction film boom of the 1950s. If Destination Moon had not appeared to have been a slam-dunk, Lippert would never had bothered to make Rocketship X-M. If both pictures, released one right after the other, had not provided the one-two punch of major unexpected financial success, studio executives would never have awakened to the fact that there was a big market for films about outer space and rockets. But once producers saw the writing on the wall, throughout the very next year, in 1951, audiences were treated to The Day the Earth Stood Still, Flight to Mars, Lost Continent, The Man from Planet X, The Thing from Another World, and When Worlds Collide. If Destination Moon had failed at the box office, George Pal’s film career could well have been over, and he may have never made When Worlds Collide and The War of the Worlds. If both those Paramount films had not succeeded, there would likely never have been Forbidden Planet or This Island Earth.

- ^ Spudis, Paul D. "Chesley Bonestell and the Landscape of the Moon." Airspacemag.com, June 14, 2012. Retrieved: January 12, 2015.

- ^ Readers may recall that the final airport scene in Casablanca also employed little people working around a cardboard cutout airplane in the foggy distance in order to give that dramatic scene depth and perspective.

- ^ Koszarski 1977, p. 68.

- ^ Buhle and Wagner 2002, p. 184.

- ^ McBride 2003, p. 462.

- ^ Lev 2003, p. 174.

- ^ Adamson 1985, p. 183.

- ^ The 1960 Destination Moon Omega Disk stereo soundtrack album (#OSL-3) liner notes include background by music-commentator Cy Schneider: "When Leith Stevens was called upon back in 1950 to compose a score for George Pal's motion picture Destination Moon, he had a peculiar creative problem on his hands. The picture dealt with man making a rocket to fly him to the moon and this science fiction fantasy itself was created to play upon inexperienced emotions by showing images never before seen. At that time, information on space, the moon's surface, rocket launchings and all the other scientific lingo that has become popular knowledge today, was considerably harder to come by. It took Stevens over three months to steep himself in enough scientific lore to prepare himself to write the first notes. He consulted with many scientists... In these conferences and by studying countless artist’s sketches of the moon’s surface, Stevens was able to discover what the space world was like. The result was a startling, particularly dramatic score which became immediately popular. The music evoked new feelings, new mental pictures ... it investigated a musical world never before probed or propounded so sharply." (Schneider, Cy. Destination Moon soundtrack liner notes, Omega Disk label stereophonic 33 1/3 LP [#OSL-3], 1960. ASIN: B002MK54BQ.)

- ^ Warren, Bill. Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of the 50s (21st century ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009. ISBN 978-0-78644-230-0.

- ^ Discogs

- ^ Crowther, Bosley. "Destination Moon (1950); The screen: Two new features arrive: 'Destination Moon,' George Pal version of 'Rocket Voyage'". The New York Times, June 28, 1950.

- ^ Journal of the British Astronomical Society, October 1950

- ^ Baxter, John. Science Fiction in the Cinema. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1970.

- ^ Asimov (1979) In Memory Yet Green, Avon Books, p. 601

- ^ Nicholls, Peter, ed. The Science Fiction Encyclopedia. New York: Doubleday, 1979. p. 166

- ^ John Clute and Peter Nicholls (Eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993. p. 324

- ^ Hardy, Phil (Ed.). The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Science Fiction. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Books, 1994. pp. 124-125

- ^ Stanley, John. Creature Features: The Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Movie Guide. New York: Berkley Boulevard Books, 2000.

- ^ From the memorial program notes for The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ George Pal: Discovering the Fantastic—A Centennial Celebration, August 27, 2008 p.2

- ^ Leonard Maltin; Spencer Green; Rob Edelman (January 2010). Leonard Maltin's Classic Movie Guide. Plume. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-452-29577-3.

- ^ Atkinson, Barry. Atomic Age Cinema: The Offbeat, the Classic and the Obscure. Baltimore: Midnight Marquee Press, 2014. atomic+age+cinema

- ^ "Destination-Moon - Cast, Crew, Director and Awards." The New York Times. Retrieved: January 12, 2015.

- ^ "1st Berlin International Film Festival: Prize Winners." Archived 2013-10-15 at the Wayback Machine Berlin International Film Festival (Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin), 2013. Retrieved: January 12, 2015.

- ^ The Hugo Awards [1] Archived 2011-05-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Hugo Awards, Retro-Hugos

- ^ "'Destination Moon' Radio broadcast (22:48)." Dimension X, NBC, June 24, 1950.

- ^ Short Stories (magazine), September 1950

- ^ "BOZO approved singles, Week 46." Archived 2007-06-29 at the Wayback Machine Kiddie Records Weekly, 2005. Retrieved: January 12, 2015.

- ^ "Fawcett: Destination Moon". Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Fawcett: Destination Moon at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

Bibliography

[edit]- Adamson. Joe The Walter Lantz Story: With Woody Woodpecker and Friends. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1985. ISBN 978-0-39913-096-0.

- Buhle, Paul and Dave Wagner. A Very Dangerous Citizen: Abraham Lincoln Polonsky and the Hollywood Left. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-52023-672-1.

- Heinlein, Robert A. "Shooting Destination Moon". Astounding Science Fiction. London: Atlas Pub. and Distributing Co., July 1950. ISSN 1059-2113.

- Hickman, Gail Morgan. The Films of George Pal. New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1977. ISBN 0-498-01960-8.

- Johnson, William. Focus on the Science Fiction Film (Illustrated ed.). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1972. ISBN 978-0-13795-179-6.

- Kondo, Yoji. Requiem: New Collected Works by Robert A. Heinlein and Tributes to the Grand Master. New York: Tom Doherty Associates, 1992. ISBN 978-0-81251-391-2.

- Koszarski, Richard. Hollywood Directors, 1941–1976. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0-19502-218-6.

- Lev, Peter. Transforming the Screen: 1950–1959. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-52024-966-0.

- McBride, Joseph. Searching For John Ford: A Life. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-31231-011-0.

- Miller, Thomas Kent. Mars in the Movies: A History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2016. ISBN 978-0-7864-9914-4.

- Parish, James Robert and Michael R. Pitts. The Great Science Fiction Pictures. Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0-81081-029-7.

- Pym, John, ed. "Destination Moon." Time Out Film Guide. London: Time Out Guides Limited, 2004. ISBN 978-0-14101-354-1.

- Schneider, Cy. Destination Moon soundtrack liner notes, Omega Disk label stereophonic 33 1/3 LP (#OSL-3), 1960. ASIN: B002MK54BQ.

- Strick, Philip. Science Fiction Movies (Illustrated ed.). London: Octopus Books 1976. ISBN 978-0-7064-0470-8.

- Warren, Bill (2009). Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of the 50s (21st century ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-78644-230-0..

External links

[edit]- 1950 films

- 1950 independent films

- 1950s science fiction films

- American films with live action and animation

- American science fiction adventure films

- American space adventure films

- Eagle-Lion Films films

- Films about astronauts

- Films adapted into comics

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on science fiction novels

- Films based on works by Robert A. Heinlein

- Films directed by Irving Pichel

- Films produced by George Pal

- Films scored by Leith Stevens

- Films set on the Moon

- Films set in outer space

- Films that won the Best Visual Effects Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Robert A. Heinlein

- Hard science fiction films

- 1950s English-language films

- 1950s American films

- Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation–winning works

- English-language science fiction films