R.E.M.

R.E.M. | |

|---|---|

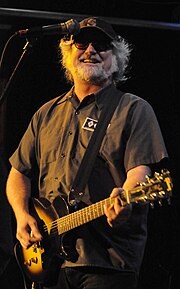

R.E.M. performing in 2003. From left to right: Mike Mills (partially cropped), Michael Stipe, touring drummer Bill Rieflin, and Peter Buck | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as |

|

| Origin | Athens, Georgia, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Discography | |

| Years active |

|

| Labels | |

| Spinoffs | |

| Past members | |

| Website | remhq |

R.E.M. was an American alternative rock band formed in Athens, Georgia in 1980 by drummer Bill Berry, guitarist Peter Buck, bassist Mike Mills, and lead vocalist Michael Stipe, who were students at the University of Georgia. One of the first alternative rock bands, R.E.M. was noted for Buck's ringing, arpeggiated guitar style; Stipe's distinctive vocal quality, unique stage presence, and obscure lyrics; Mills's melodic bass lines and backing vocals; and Berry's tight, economical drumming style. In the early 1990s, other alternative rock acts such as Nirvana, Pixies and Pavement viewed R.E.M. as a pioneer of the genre. After Berry left in 1997, the band continued with mixed critical and commercial success. The band broke up amicably in 2011, having sold more than 90 million albums worldwide and becoming one of the world's best-selling music acts.

The band released their first single, "Radio Free Europe", in 1981 on the independent record label Hib-Tone. It was followed by the Chronic Town EP in 1982, their first release on I.R.S. Records. Over the course of the decade, R.E.M. released acclaimed albums, commencing with their debut Murmur (1983), and continuing yearly with Reckoning (1984), Fables of the Reconstruction (1985), Lifes Rich Pageant (1986), Document (1987) and Green (1988). During their most successful period, they worked with the producer Scott Litt. With constant touring, and the support of college radio following years of underground success, R.E.M. achieved a mainstream hit with the 1987 single "The One I Love". They signed to Warner Bros. Records in 1988, and began to espouse political and environmental concerns while playing arenas worldwide.

R.E.M.'s most commercially successful albums, Out of Time (1991) and Automatic for the People (1992), put them in the vanguard of alternative rock as it was becoming mainstream. Out of Time received seven nominations at the 34th Annual Grammy Awards, and the lead single, "Losing My Religion", was R.E.M.'s highest-charting and best-selling hit. Monster (1994) continued its run of success. The band began its first tour in six years to support the album; the tour was marred by medical emergencies suffered by three of the band members. In 1996, R.E.M. re-signed with Warner Bros. for a reported US$80 million, at the time the most expensive recording contract ever. The tour was productive and the band recorded the following album mostly during soundchecks. The resulting record, New Adventures in Hi-Fi (1996), is hailed as the band's last great album and the members' favorite, growing in cult status over the years. Berry left the band the following year, and Stipe, Buck and Mills continued as a musical trio, supplemented by studio and live musicians, such as the multi-instrumentalists Scott McCaughey and Ken Stringfellow and the drummers Joey Waronker and Bill Rieflin. They also parted ways with their longtime manager Jefferson Holt, at which point the band's attorney Bertis Downs assumed managerial duties. Seeking to also renovate their sound, the band stopped working with Litt, and hired as co-producer Pat McCarthy, who had worked as mixer and engineer on the band's previous two albums.

After the electronic experimental direction of Up (1998), which was commercially unsuccessful, Reveal (2001), referred to as "a conscious return to their classic sound",[2] received general acclaim. In 2007, the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in its first year of eligibility. Berry reunited with the band for the ceremony, and to record a cover of John Lennon's "#9 Dream" for the 2007 compilation album Instant Karma: The Amnesty International Campaign to Save Darfur to benefit Amnesty International's campaign to alleviate the Darfur conflict. Looking for a change of sound after lukewarm reception for Around the Sun (2004), the band collaborated with the producer Jacknife Lee on their final two studio albums—the well-received Accelerate (2008) and Collapse into Now (2011). In 2024, the band reunited to perform "Losing My Religion" at their induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame.[3]

History

[edit]1980–1982: Formation and first releases

[edit]

In January 1980, Peter Buck met Michael Stipe in Wuxtry Records, the Athens record store where Buck worked. The pair discovered that they shared similar tastes in music, particularly in punk rock and proto-punk artists like Patti Smith, Television, and the Velvet Underground. Stipe said, "It turns out that I was buying all the records that [Buck] was saving for himself."[4] Through mutual friend Kathleen O'Brien,[5] Stipe and Buck then met fellow University of Georgia students Bill Berry and Mike Mills,[6] who had played music together since high school[7]: 30 and had lived together in Macon, Georgia.[8] The quartet agreed to collaborate on several songs; Stipe later commented that "there was never any grand plan behind any of it".[4] Their still-unnamed band spent a few months rehearsing in the deconsecrated St. Mary's Episcopal Church on Oconee Street in Athens. "I remember our very first practice," recalled Mills in 2024. "Bill and I had some stuff left over from our band in Macon. We showed it to Peter and Michael, and they took it to places—even that very first night—that I didn't expect. I thought, 'This works for me.'"[9] He continued: "Bill and I had a bunch of songs from a band we were in in Macon, and we showed [Peter and Michael] those songs. Peter was playing arpeggiated stuff – nobody plays that. And Michael: the voice was there, and he did some fun things with the melodies. I thought, 'These guys are bringing something to the game.'"[10] They fleshed out their performances at their rehearsal space, on Jackson Street in Athens.[10]

They played their first show on April 5, 1980, who were supported by the Side Effects at O'Brien's birthday party held in the same church, performing a mix of originals and 1960s and 1970s covers.[5] After considering names such as "Cans of Peas", “Negro Wives”, “Slug Bank”, and “The Dry Sundaes”,[5] the band settled on "R.E.M.", which Stipe selected at random from a dictionary.[7]: 39 R.E.M. is well known as an abbreviation for rapid eye movement, the dream stage of sleep; however, sleep researcher Rafael Pelayo reports that when his colleague William Dement, the sleep scientist who coined the term REM, reached out to the band, Dement was told that the band was named "not after REM sleep".[11]

The band members eventually dropped out of school to focus on their developing group.[12] They found a manager in Jefferson Holt, a record store clerk who was so impressed by an R.E.M. performance in his hometown of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, that he moved to Athens.[7]: 41 R.E.M.'s success was almost immediate in Athens and surrounding areas; the band drew progressively larger crowds for shows, which caused some resentment in the Athens music scene.[7]: 46 Over the next year and a half, R.E.M. toured throughout the Southern United States. Touring was arduous because a touring circuit for alternative rock bands did not then exist. The group toured in an old blue van driven by Holt (and any band member except Stipe),[10] and lived on a food allowance of $2 each per day.[7]: 53–54

During April 1981, R.E.M. recorded their first single, "Radio Free Europe", at producer Mitch Easter's Drive-In Studio in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, after a recommendation by Peter Holsapple.[13] Initially distributing it as a four-track demo tape to clubs, record labels and magazines, the single was released in July 1981 on the local independent record label Hib-Tone with an initial pressing of 1,000 copies—600 of which were sent out as promotional copies. The single quickly sold out, and another 6,000 copies were pressed due to popular demand, despite the original pressing leaving off the record label's contact details.[14][5] Despite its limited pressing, the single garnered critical acclaim, and was listed as one of the ten best singles of the year by The New York Times.[1]: 497

R.E.M. recorded the Chronic Town EP with Mitch Easter in October 1981, and planned to release it on a new indie label named Dasht Hopes.[7]: 59 However, I.R.S. Records acquired a demo of the band's first recording session with Easter that had been circulating for months.[7]: 61–63 The band turned down the advances of major label RCA Records in favor of I.R.S., with whom they signed a contract in May 1982. I.R.S. released Chronic Town that August as its first American release.[7]: 66–67 A positive review of the EP by NME praised the songs' auras of mystery, and concluded, "R.E.M. ring true, and it's great to hear something as unforced and cunning as this."[16]

1982–1988: I.R.S. Records and cult success

[edit]I.R.S. first paired R.E.M. with producer Stephen Hague to record their debut album. Hague's emphasis on technical perfection left the band unsatisfied, and the band members asked the label to let them record with Easter.[7]: 72 I.R.S. agreed to a "tryout" session, allowing the band to return to North Carolina and record the song "Pilgrimage" with Easter and producing partner Don Dixon. After hearing the track, I.R.S. permitted the group to record the album with Dixon and Easter.[7]: 78 Because of their bad experience with Hague, the band recorded the album via a process of negation, refusing to incorporate rock music clichés such as guitar solos or then-popular synthesizers, in order to give its music a timeless feel.[7]: 78–82 The completed album, Murmur, was greeted with critical acclaim upon its release in 1983, with Rolling Stone listing the album as its record of the year.[7]: 73 The album reached number 36 on the Billboard album chart.[7]: 357–58 A re-recorded version of "Radio Free Europe" was the album's lead single and reached number 78 on the Billboard singles chart in 1983.[17] Despite the acclaim awarded the album, Murmur sold only about 200,000 copies, which I.R.S.'s Jay Boberg felt was below expectations.[7]: 95

R.E.M. made their first national television appearance on Late Night with David Letterman in October 1983,[1]: 432 during which the group performed a new, unnamed song.[1]: 434 The piece, eventually titled "So. Central Rain (I'm Sorry)", became the first single from the band's second album, Reckoning (1984), which was also recorded with Easter and Dixon. The album met with critical acclaim; NME's Mat Snow wrote that Reckoning "confirms R.E.M. as one of the most beautifully exciting groups on the planet".[18] While Reckoning peaked at number 27 on the US album charts—an unusually high chart placing for a college rock band at the time—scant airplay and poor distribution overseas resulted in it charting no higher than number 91 in Britain.[7]: 115

The band's third album, Fables of the Reconstruction (1985), demonstrated a change in direction. Instead of Dixon and Easter, R.E.M. chose producer Joe Boyd, who had worked with Fairport Convention and Nick Drake, to record the album in England. The band members found the sessions unexpectedly difficult, and were miserable due to the cold winter weather and what they considered to be poor food;[7]: 131–132 the situation brought the band to the verge of break-up.[7]: 135 The gloominess surrounding the sessions worked its way into the context for the album's themes. Lyrically, Stipe began to create storylines in the mode of Southern mythology, noting in a 1985 interview that he was inspired by "the whole idea of the old men sitting around the fire, passing on ... legends and fables to the grandchildren".[19]

They toured Canada in July and August 1985, and Europe in October of that year, including the Netherlands, England (including one concert at London's Hammersmith Palais), Ireland, Scotland, France, Switzerland, Belgium, and West Germany.[20] On October 2, 1985, the group played a concert in Bochum, West Germany, for the German TV show Rockpalast. Stipe had bleached his hair blond during this time.[21][22] R.E.M. invited California punk band Minutemen to open for them on part of the US tour, and organized a benefit for the family of Minutemen frontman D. Boon who died in a December 1985 car crash shortly after the tour's conclusion.[23] Fables of the Reconstruction performed poorly in Europe and its critical reception was mixed, with some critics regarding it as dreary and poorly recorded.[7]: 140 As with the previous records, the singles from Fables of the Reconstruction were mostly ignored by mainstream radio. Meanwhile, I.R.S. was becoming frustrated with the band's reluctance to achieve mainstream success.[7]: 159

For their fourth album, R.E.M. enlisted John Mellencamp's producer Don Gehman. The album, entitled Lifes Rich Pageant (1986), featured Stipe's vocals closer to the forefront of the music. In a 1986 interview with the Chicago Tribune, Peter Buck related, "Michael is getting better at what he's doing, and he's getting more confident at it. And I think that shows up in the projection of his voice."[24] The album improved markedly upon the sales of Fables of the Reconstruction and reached number 21 on the Billboard album chart. The single "Fall on Me" also picked up support on commercial radio.[7]: 151 The album was the band's first to be certified gold for selling 500,000 copies.[25]: 142 While American college radio remained R.E.M.'s core support, the band was beginning to chart hits on mainstream rock formats; however, the music still encountered resistance from Top 40 radio.[7]: 160

Following the success of Lifes Rich Pageant, I.R.S. issued Dead Letter Office, a compilation of tracks recorded by the band during their album sessions, many of which had either been issued as B-sides or left unreleased altogether. Shortly thereafter, I.R.S. compiled R.E.M.'s music video catalog (except "Wolves, Lower") as the band's first video release, Succumbs.

Don Gehman was unable to produce R.E.M.'s fifth album, so he suggested the group work with Scott Litt.[25]: 146 Litt would be the producer for the band's next five albums. Document (1987) featured some of Stipe's most openly political lyrics, particularly on "Welcome to the Occupation" and "Exhuming McCarthy", which were reactions to the conservative political environment of the 1980s under American president Ronald Reagan.[26] Jon Pareles of The New York Times wrote in his review of the album, "'Document' is both confident and defiant; if R.E.M. is about to move from cult-band status to mass popularity, the album decrees that the band will get there on its own terms."[27] Document was R.E.M.'s breakthrough album, and the first single "The One I Love" charted in the Top 20 in the US, UK, and Canada.[7]: 357–58 By January 1988, Document had become the group's first album to sell a million copies.[25]: 157 In light of the band's breakthrough, the December 1987 cover of Rolling Stone declared R.E.M. "America's Best Rock & Roll Band".[7]: 163

1988–1997: International breakout and alternative rock stardom

[edit]Frustrated that its records did not see satisfactory overseas distribution, R.E.M. left I.R.S. when its contract expired and signed with the major label Warner Bros. Records.[7]: 174 Though other labels offered more money, R.E.M. ultimately signed with Warner Bros.—reportedly for an amount between $6 million and $12 million—due to the company's assurance of total creative freedom. (Jay Boberg claimed that R.E.M.'s deal with Warner Bros. was for $22 million, which Peter Buck disputed as "definitely wrong".)[7]: 177 In the aftermath of the group's departure, I.R.S. released the 1988 "best of" compilation Eponymous (assembled with input from the band members) to capitalize on assets the company still possessed.[25]: 170–171 The band's first album from Warner Bros., Green (1988), was recorded in Memphis, Tennessee, and showcased the group experimenting with its sound.[7]: 179 The record's tracks ranged from the upbeat first single "Stand" (a hit in the United States),[7]: 180 to more political material, like the rock-oriented "Orange Crush" and "World Leader Pretend", which address the Vietnam War and the Cold War, respectively.[7]: 183 Green has gone on to sell four million copies worldwide.[25]: 296 The band supported the album with their biggest and most visually developed tour to date, featuring back-projections and art films playing on the stage.[7]: 184 After the Green World Tour, the band members unofficially decided to take the following year off, the first extended break in the band's career.[7]: 198 In 1990, Warner Bros. issued the music video compilation Pop Screen to collect clips from the Document and Green albums, followed a few months later by the video album Tourfilm featuring live performances filmed during the Green World Tour.[25]: 181

R.E.M. reconvened in mid 1990 to record their seventh album, Out of Time. In a departure from Green, the band members often wrote the music with non-traditional rock instrumentation including mandolin, organ, and acoustic guitar instead of adding them as overdubs later in the creative process.[7]: 209 [28] Released in March 1991, Out of Time was the band's first album to top both the US and UK charts.[7]: 357–58 The record eventually sold 4.2 million copies in the US alone,[7]: 287 and about 12 million copies worldwide by 1996.[25]: 296 The album's lead single, "Losing My Religion", was a worldwide hit that received heavy rotation on radio, as did the music video on MTV and VH1.[7]: 205 "Losing My Religion" was also R.E.M.'s highest-charting single in the US, reaching number four on the Billboard charts.[7]: 357–58 "There've been very few life-changing events in our career because our career has been so gradual," Mills said years later. In 2024, he added: "If we'd sold ten million of our first record, I doubt any of us would be alive right now."[29] Regarding a pivotal moment, he said: "If you want to talk about life changing, I think 'Losing My Religion' is the closest it gets".[7]: 204 The album's second single, "Shiny Happy People"—one of three songs on the record to feature vocals from Kate Pierson of fellow Athens band the B-52's, was also a major hit, reaching number 10 in the US and number six in the UK.[7]: 357–58 Out of Time garnered R.E.M. seven nominations at the 1992 Grammy Awards, the most nominations of any artist that year. The band won three awards: one for Best Alternative Music Album and two for "Losing My Religion", Best Short Form Music Video and Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal.[30] R.E.M. did not tour to promote Out of Time; instead, the band played a series of one-off shows, including an appearance taped for an episode of MTV Unplugged[7]: 213 and released music videos for each song on the video album This Film Is On. The band also performed "Losing My Religion" with members of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra at Madison–Morgan Cultural Center, in Madison, Georgia, as part of MTV's 10th-anniversary special.[31]

After spending some months off, R.E.M. returned to the studio in 1991 to record their next album. In late 1992, the band released Automatic for the People. Even though the group had intended to make a harder-rocking album after the softer textures of Out of Time,[7]: 216 the somber Automatic for the People "[seemed] to move at an even more agonized crawl", according to Melody Maker.[32] The album dealt with themes of loss and mourning inspired by "that sense of ... turning thirty", according to Buck.[7]: 218 Several songs featured string arrangements by former Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones. Considered by a number of critics (as well as by Buck and Mills) to be the band's best album,[7]: 217 Automatic for the People reached numbers one and two on UK and US charts, respectively, and generated the American Top 40 hit singles "Drive", "Man on the Moon", and "Everybody Hurts".[7]: 357–58 The album would sell over fifteen million copies worldwide.[25]: 296 As with Out of Time, there was no tour in support of the album. The decision to forgo a tour, in conjunction with Stipe's physical appearance, generated rumors that the singer was dying or HIV-positive, which were vehemently denied by the band.[32]

After the band released two slow-paced albums in a row, R.E.M.'s 1994 album Monster was, as Buck said, "a 'rock' record, with the rock in quotation marks." In contrast to the sound of its predecessors, the music of Monster consisted of distorted guitar tones, minimal overdubs, and touches of 1970s glam rock.[7]: 236 Like Out of Time, Monster topped the charts in both the US and UK.[7]: 357–58 The record sold about nine million copies worldwide.[25]: 296 The singles "What's the Frequency, Kenneth?" and "Bang and Blame" were the band's last American Top 40 hits, although all the singles from Monster reached the Top 30 on the British charts.[7]: 357–58 Warner Bros. assembled the music videos from the album as well as those from Automatic for the People for release as Parallel in 1995.[25]: 270

In January 1995, R.E.M. set out on its first tour in six years. The tour was a huge commercial success, but the period was difficult for the group.[7]: 248 On March 1, Berry collapsed on stage during a performance in Lausanne, Switzerland, having suffered a brain aneurysm. He had surgery immediately and recovered fully within a month. Berry's aneurysm was only the beginning of a series of health problems that plagued the Monster tour. Mills had to undergo abdominal surgery to remove an intestinal adhesion in July; a month later, Stipe had to have an emergency surgery to repair a hernia.[7]: 251–255 Despite all the problems, the group had recorded the bulk of a new album while on the road. The band brought along eight-track recorders to capture its shows, and used the recordings as the base elements for the album.[7]: 256 The final three performances of the tour were filmed at the Omni Coliseum in Atlanta, Georgia and released in home video form as Road Movie.[25]: 274

R.E.M. re-signed with Warner Bros. Records in 1996 for a reported $80 million (a figure the band constantly asserted originated with the media), rumored to be the largest recording contract in history at that point.[7]: 258 The group's 1996 album New Adventures in Hi-Fi debuted at number two in the US and number one in the UK.[7]: 357–58 The five million copies of the album sold were a reversal of the group's commercial fortunes of the previous five years.[7]: 269 Critical reaction to the album was mostly favorable. In a 2017 retrospective on the band, Consequence of Sound ranked it third out of R.E.M.'s 15 full-length studio albums.[33] The album is Stipe's favorite from R.E.M. and he considers it the band at their peak.[34] Mills says, "It usually takes a good few years for me to decide where an album stands in the pantheon of recorded work we've done. This one may be third behind Murmur and Automatic for the People.[35] According to DiscoverMusic: "Arguably less immediate and less accessible [...] New Adventures in Hi-Fi is a sprawling, "White Album"-esque affair clocking in at 65 minutes. However, while it required some time and commitment from the listener, the record's contents were rich, compelling and frequently stunning. Accordingly, the album has continued to lobby for recognition and has long since earned its reputation as R.E.M.'s most unsung LP."[36] While sales were impressive, they were below their previous major label records. Time's writer Christopher John Farley argued that the lesser sales of the album were due to the declining commercial power of alternative rock as a whole.[37] That same year, R.E.M. parted ways with manager Jefferson Holt, allegedly due to sexual harassment charges levied against him by a member of the band's home office in Athens.[38] The group's lawyer Bertis Downs assumed managerial duties.[7]: 259

1997–2006: Continuing as three-piece with mixed success

[edit]In April 1997, the band convened at Buck's Kauai vacation home to record demos of material intended for the next album. The band sought to reinvent its sound and intended to incorporate drum loops and percussion experiments.[39] Just as the sessions were due to begin in October, Berry decided, after months of contemplation and discussions with Downs and Mills, to tell the rest of the band that he was quitting.[7]: 276 Berry told his bandmates that he would not quit if they would break up as a result, so Stipe, Buck, and Mills agreed to carry on as a three-piece with his blessing.[7]: 280 Berry publicly announced his departure three weeks later in October 1997. Berry told the press, "I'm just not as enthusiastic as I have been in the past about doing this anymore . . . I have the best job in the world. But I'm kind of ready to sit back and reflect and maybe not be a pop star anymore."[39] Stipe admitted that the band would be different without a major contributor: "For me, Mike, and Peter, as R.E.M., are we still R.E.M.? I guess a three-legged dog is still a dog. It just has to learn to run differently."[7]: 280

The band cancelled their scheduled recording sessions as a result of Berry's departure. "Without Bill it was different, confusing", Mills later said. "We didn't know exactly what to do. We couldn't rehearse without a drummer."[40]: 232 The remaining members of R.E.M. resumed work on the album in February 1998 at Toast Studios in San Francisco.[40]: 233 The band ended their decade-long collaboration with Scott Litt and hired Pat McCarthy to produce the record. Nigel Godrich was taken on as assistant producer, and drafted in Screaming Trees member Barrett Martin and Beck's touring drummer Joey Waronker. The recording process was tense, and the group came close to disbanding. Bertis Downs called an emergency meeting in which the band members resolved their problems and agreed to continue as a group.[7]: 286 Led by the single "Daysleeper", Up (1998) debuted in the top ten in the US and UK. However, the album was a relative failure, selling 900,000 copies in the US by mid-1999 and eventually selling just over two million copies worldwide.[7]: 287 While R.E.M.'s American sales were declining, the group's commercial base was shifting to the UK, where more R.E.M. records were sold per capita than any other country and the band's singles regularly entered the Top 20.[7]: 292

A year after Up's release, R.E.M. wrote the instrumental score to the Andy Kaufman biographical film Man on the Moon, a first for the group. The film took its title from the Automatic for the People song of the same name.[41] The song "The Great Beyond" was released as a single from the Man on the Moon soundtrack album. "The Great Beyond" only reached number 57 on the American pop charts, but was the band's highest-charting single ever in the UK, reaching number three in 2000.[7]: 357–58

R.E.M. recorded the majority of their twelfth album Reveal (2001) in Canada and Ireland from May to October 2000.[40]: 248–249 Reveal shared the "lugubrious pace" of Up,[7]: 303 and featured drumming by Joey Waronker, as well as contributions by Scott McCaughey (a co-founder of the band the Minus 5 with Buck), and Ken Stringfellow (founder of the Posies). Global sales of the album were over four million, but in the United States Reveal sold about the same number of copies as Up.[7]: 310 The album was led by the single "Imitation of Life", which reached number six in the UK.[7]: 305 Writing for Rock's Backpages, The Rev. Al Friston described the album as "loaded with golden loveliness at every twist and turn", in comparison to the group's "essentially unconvincing work on New Adventures in Hi-Fi and Up".[42] Similarly, Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone called Reveal "a spiritual renewal rooted in a musical one" and praised its "ceaselessly astonishing beauty".[43]

In 2003, Warner Bros. released the compilation album and DVD In Time: The Best of R.E.M. 1988–2003 and In View: The Best of R.E.M. 1988–2003, which featured two new songs, "Bad Day" and "Animal". At a 2003 concert in Raleigh, North Carolina, Berry made a surprise appearance, performing backing vocals on "Radio Free Europe". He then sat behind the drum kit for a performance of the early R.E.M. song "Permanent Vacation", marking his first performance with the band since his retirement.[44][45]

R.E.M. released Around the Sun in 2004. During production of the album in 2002, Stipe said, "[The album] sounds like it's taking off from the last couple of records into unchartered R.E.M. territory. Kind of primitive and howling".[46] After the album's release, Mills said, "I think, honestly, it turned out a little slower than we intended for it to, just in terms of the overall speed of songs."[47] Around the Sun received a mixed critical reception, and peaked at number 13 on the Billboard charts.[48] The first single from the album, "Leaving New York", was a Top 5 hit in the UK.[49] For the record and subsequent tour, the band hired a new full-time touring drummer, Bill Rieflin, who had previously been a member of several industrial music acts such as Ministry and Pigface, and remained in that role for the duration of the band's active years.[50] The video album Perfect Square was released that same year.

2006–2011: Last albums, recognition and breakup

[edit]

EMI released a compilation album covering R.E.M.'s work during its tenure on I.R.S. in 2006 called And I Feel Fine... The Best of the I.R.S. Years 1982–1987 along with the video album When the Light Is Mine: The Best of the I.R.S. Years 1982–1987—the label had previously released the compilations The Best of R.E.M. (1991), R.E.M.: Singles Collected (1994), and R.E.M.: In the Attic – Alternative Recordings 1985–1989 (1997). That same month, all four original band members performed during the ceremony for their induction into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame.[51] While rehearsing for the ceremony, the band recorded a cover of John Lennon's "#9 Dream" for Instant Karma: The Amnesty International Campaign to Save Darfur, a tribute album benefiting Amnesty International.[52] The song—released as a single for the album and the campaign—featured Bill Berry's first studio recording with the band since his departure almost a decade earlier.[53]

In October 2006, R.E.M. was nominated for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in their first year of eligibility.[54] The band was one of five nominees accepted into the Hall that year, and the induction ceremony took place in March 2007 at New York's Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The group—which was inducted by Pearl Jam lead singer Eddie Vedder—performed three songs with Bill Berry; "Gardening at Night", "Man on the Moon" and "Begin the Begin" as well as a cover of "I Wanna Be Your Dog".[55]

Work on the group's fourteenth album commenced in early 2007. The band recorded with producer Jacknife Lee in Vancouver and Dublin, where it played five nights in the Olympia Theatre between June 30 and July 5 as part of a "working rehearsal".[56] R.E.M. Live, the band's first live album (featuring songs from a 2005 Dublin show), was released in October 2007.[57] The group followed this with the 2009 live album Live at The Olympia, which features performances from its 2007 residency. R.E.M. released Accelerate in early 2008. The album debuted at number two on the Billboard charts,[58] and became the band's eighth album to top the British album charts.[59] Rolling Stone reviewer David Fricke considered Accelerate an improvement over the band's previous post-Berry albums, calling it "one of the best records R.E.M. have ever made".[60]

In 2010, R.E.M. released the video album R.E.M. Live from Austin, TX—a concert recorded for Austin City Limits in 2008. The group recorded its fifteenth album, Collapse into Now (2011), with Jacknife Lee in locales including Berlin, Nashville, and New Orleans. For the album, the band aimed for a more expansive sound than the intentionally short and speedy approach implemented on Accelerate.[61] The album debuted at number five on the Billboard 200, becoming the group's tenth album to reach the top ten of the chart.[62] This release fulfilled R.E.M.'s contractual obligations to Warner Bros., and the band began recording material without a contract a few months later with the possible intention of self-releasing the work.[63]

On September 21, 2011, R.E.M. announced via its website that it was "calling it a day as a band". Stipe said that he hoped fans realized it "wasn't an easy decision": "All things must end, and we wanted to do it right, to do it our way."[64] Long-time associate and former Warner Bros. Senior Vice President of Emerging Technology Ethan Kaplan has speculated that shake-ups at the record label influenced the group's decision to disband.[65] The group discussed breaking up for several years, but was encouraged to continue after the lackluster critical and commercial performance of Around the Sun; according to Mills, "We needed to prove, not only to our fans and critics but to ourselves, that we could still make great records."[66] They were also uninterested in the business end of recording as R.E.M.[67] The band members finished their collaboration by assembling the compilation album Part Lies, Part Heart, Part Truth, Part Garbage 1982–2011, which was released in November 2011. The album is the first to collect songs from R.E.M.'s I.R.S. and Warner Bros. tenures, as well as three songs from the group's final studio recordings from post-Collapse into Now sessions.[68] In November, Mills and Stipe did a brief span of promotional appearances in British media, ruling out the option of the group ever reuniting.[69]

In 2024, during their first interview as a foursome in 27 years, the band was asked what it would take for them to re-form. "A comet," replied Mills. "Superglue," added Berry. When asked why it would not happen, Buck stated, "It would never be as good."[70]

2011–present: Post-breakup releases and events

[edit]In 2014, Unplugged: The Complete 1991 and 2001 Sessions was released for Record Store Day.[71] Download collections of I.R.S. and Warner Bros. rarities followed. Later in the year, R.E.M. compiled the video album box set REMTV, which collected their two Unplugged performances along with several other documentaries and live shows, while their record label released the box set 7IN—83–88, made up of 7-inch vinyl singles.[72] In December 2015, the band members agreed to a distribution deal with Concord Bicycle Music to re-release their Warner Bros. albums.[73]

In March 2016, R.E.M. signed a publishing administration deal with Universal Music Publishing Group.[74] In March 2017, R.E.M. left Broadcast Music, Inc., who had represented their performance rights for their entire career, and joined SESAC.[75] The first release under SESAC was the 2018 box set R.E.M. at the BBC, followed in 2019 by Live at the Borderline 1991 for Record Store Day. On March 24, 2020, Rieflin died of cancer.[76]

In October 2019, during the presentation of his book of photographs in Rome, Michael Stipe said: "I'm having dinner with Mike (Mills) just tomorrow night in London and I spoke to Peter (Buck) last night, we're good friends but R.E.M.'s time it's over, that's it".[77]

In September 2021, a decade after disbanding, Stipe reiterated that R.E.M. had no intention of regrouping: "We decided when we split up that that would just be really tacky and probably money-grabbing, which might be the impetus for a lot of bands to get back together."[78] In 2023, R.E.M. was nominated for induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame[79] and were inducted in June 2024.[80] To mark this occasion, on 13 June 2024, all four founding members reunited for their first public live performance since 2007 and performed an acoustic rendition of "Losing My Religion" in New York City.[81][82]

Musical style

[edit]Sound and songwriting process

[edit]R.E.M.'s music has been described as alternative rock,[83] college rock,[84] folk rock,[85] jangle pop,[86] post-punk,[86] and new wave.[87] In a 1988 interview, Peter Buck described R.E.M. songs as typically, "Minor key, mid-tempo, enigmatic, semi-folk-rock-balladish things. That's what everyone thinks and to a certain degree, that's true."[88]

All songwriting is credited to the entire band, even though individual members are sometimes responsible for writing the majority of a particular song.[89] Each member is given an equal vote in the songwriting process; however, Buck has conceded that Stipe, as the band's lyricist, can rarely be persuaded to follow an idea he does not favor.[32] Among the original line-up, there were divisions of labor in the songwriting process: Stipe would write lyrics and devise melodies, Buck would edge the band in new musical directions, and Mills and Berry would fine-tune the compositions due to their greater musical experience.[7]: 85 Regarding Buck's driven approach, Mills said: "Someone's got to drive the train, and we were all more than happy to have Peter be our motivator." Stipe added, addressing Buck: "There's a body of work that wouldn't be there had you not been pushing us as hard as you did."[90]

Vocals and lyrics

[edit]Michael Stipe sings in what R.E.M. biographer David Buckley described as "wailing, keening, arching vocal figures".[7]: 87 Stipe often harmonizes with Mills in songs; in the chorus for "Stand", Mills and Stipe alternate singing lyrics, creating a dialogue.[7]: 180–181 Early articles about the band focused on Stipe's singing style (described as "mumbling" by The Washington Post), which often rendered his lyrics indecipherable.[15] Creem writer John Morthland wrote in his review of Murmur, "I still have no idea what these songs are about, because neither me nor anyone else I know has ever been able to discern R.E.M.'s lyrics."[91] Stipe commented in 1984, "It's just the way I sing. If I tried to control it, it would be pretty false."[92] Producer Joe Boyd convinced Stipe to begin singing more clearly during the recording of Fables of the Reconstruction.[7]: 133

Stipe referred to the lyrics in the chorus of "Sitting Still" from R.E.M.'s debut album, Murmur, "nonsense", saying in a 1994 online chat, "You all know there aren't words, per se, to a lot of the early stuff. I can't even remember them." In truth, Stipe carefully crafted the lyrics to many early R.E.M. songs.[7]: 88 Stipe explained in 1984 that when he started writing lyrics they were like "simple pictures", but after a year he grew tired of the approach and "started experimenting with lyrics that didn't make exact linear sense, and it's just gone from there."[92] In the mid-1980s, as Stipe's pronunciation while singing became clearer, the band decided that its lyrics should convey ideas on a more literal level.[7]: 143 Mills explained, "After you've made three records and you've written several songs and they've gotten better and better lyrically the next step would be to have somebody question you and say, are you saying anything? And Michael had the confidence at that point to say yes . . ."[7]: 150 Songs like "Cuyahoga" and "Fall on Me" on Lifes Rich Pageant dealt with such concerns as pollution.[7]: 156–157 Stipe incorporated more politically oriented concerns into his lyrics on Document and Green. "Our political activism and the content of the songs was just a reaction to where we were, and what we were surrounded by, which was just abject horror," Stipe said later. "In 1987 and '88 there was nothing to do but be active."[93] Stipe has since explored other lyrical topics. Automatic for the People dealt with "mortality and dying. Pretty turgid stuff", according to Stipe,[94] while Monster critiqued love and mass culture.[93] Musically, Stipe stated that bands like T. Rex and Mott the Hoople "really impacted me".[95]

Instrumentation

[edit]Peter Buck's style of playing guitar has been singled out by many as the most distinctive aspect of R.E.M.'s music. During the 1980s, Buck's "economical, arpeggiated, poetic" style reminded British music journalists of 1960s American folk rock band the Byrds.[7]: 77 Buck has stated "[Byrds guitarist] Roger McGuinn was a big influence on me as a guitar player",[7]: 81 but said it was Byrds-influenced bands, including Big Star and the Soft Boys, that inspired him more.[25]: 115 Comparisons were also made with the guitar playing of Johnny Marr of alternative rock contemporaries the Smiths. While Buck professed being a fan of the group, he admitted he initially criticized the band simply because he was tired of fans asking him if he was influenced by Marr,[89] whose band had in fact made their debut after R.E.M.[25]: 115 Buck generally eschews guitar solos; he explained in 2002, "I know that when guitarists rip into this hot solo, people go nuts, but I don't write songs that suit that, and I am not interested in that. I can do it if I have to, but I don't like it."[7]: 80 Mike Mills' melodic approach to bass playing is inspired by Paul McCartney of the Beatles and Chris Squire of Yes; Mills has said, "I always played a melodic bass, like a piano bass in some ways . . . I never wanted to play the traditional locked into the kick drum, root note bass work."[7]: 105 Mills has more musical training than his bandmates, which he has said "made it easier to turn abstract musical ideas into reality."[7]: 81

Legacy and influence

[edit]

R.E.M. was pivotal in the creation and development of the alternative rock genre. AllMusic stated, "R.E.M. mark the point when post-punk turned into alternative rock."[12] In the early 1980s, the musical style of R.E.M. stood in contrast to the post-punk and new wave genres that had preceded it. Music journalist Simon Reynolds noted that the post-punk movement of the late 1970s and early 1980s "had taken whole swaths of music off the menu", particularly that of the 1960s, and that "After postpunk's demystification and New Pop's schematics, it felt liberating to listen to music rooted in mystical awe and blissed-out surrender." Reynolds declared R.E.M., a band that recalled the music of the 1960s with its "plangent guitar chimes and folk-styled vocals" and who "wistfully and abstractly conjured visions and new frontiers for America", one of "the two most important alt-rock bands of the day."[96] With the release of Murmur, R.E.M. had the most impact musically and commercially of the developing alternative genre's early groups, leaving in its wake a number of jangle pop followers.[97]

R.E.M.'s early breakthrough success served as an inspiration for other alternative bands. Spin referred to the "R.E.M. model"—career decisions that R.E.M. made that set guidelines for other underground artists to follow in their own careers. Spin's Charles Aaron wrote that by 1985, "They'd shown how far an underground, punk-inspired rock band could go within the industry without whoring out its artistic integrity in any obvious way. They'd figured out how to buy in, not sellout-in other words, they'd achieved the American Bohemian Dream."[98] Steve Wynn of Dream Syndicate said, "They invented a whole new ballgame for all of the other bands to follow whether it was Sonic Youth or the Replacements or Nirvana or Butthole Surfers. R.E.M. staked the claim. Musically, the bands did different things, but R.E.M. was first to show us you can be big and still be cool."[99] Biographer David Buckley stated that between 1991 and 1994, a period that saw the band sell an estimated 30 million albums, R.E.M. "asserted themselves as rivals to U2 for the title of biggest rock band in the world."[7]: 200 Over the course of its career, the band has sold over 85 million records worldwide.[100] Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums stated that "Their catalogue is destined to endure as critics reluctantly accept their considerable importance in the history of rock".[101]

Numerous alternative bands have cited R.E.M. as an influence, including Nirvana, Pavement, Radiohead,[102] Pearl Jam (the band's vocalist Eddie Vedder inducted R.E.M. into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame),[103] Live,[104] Collective Soul,[103] Alice in Chains,[103] and Liz Phair.[105] "When I was 15 years old in Richmond, Virginia, they were a very important part of my life," Pavement's Bob Nastanovich said, "as they were for all the members of our band."[106] Pavement's contribution to the No Alternative compilation (1993) was "Unseen Power of the Picket Fence", a song about R.E.M.'s early days.[107] Local H, according to the band's Twitter account, created their name by combining two R.E.M. songs: "Oddfellows Local 151" and "Swan Swan H".[108] Black Francis of the Pixies has described Murmur as "hugely influential" on his songwriting.[109] Kurt Cobain of Nirvana was a fan of R.E.M., and had unfulfilled plans to collaborate on a musical project with Stipe.[7]: 239–240 Cobain told Rolling Stone in a 1994 interview, "I don't know how that band does what they do. God, they're the greatest. They've dealt with their success like saints, and they keep delivering great music."[110]

During his show at the 40 Watt Club in October 2018, Johnny Marr said: "As a British musician coming out of the indie scene in the early '80s, which I definitely am and am proud to have been, I can't miss this opportunity to acknowledge and pay my respects and honor the guys who put this town on the map for us in England. I'm talking about my comrades in guitar music, R.E.M. The Smiths really respected R.E.M. We had to keep an eye on what those guys were up to. It's an interesting thing for me, as a British musician, and all those guys as British musicians, to come to this place and play for you guys, knowing that it's the roots of Mike Mills and Bill Berry and Michael Stipe and my good friend Peter Buck."[111] On November 3, 2023, the former Monkees member Micky Dolenz released an EP of R.E.M. cover songs.[112][113]

Awards

[edit]Campaigning and activism

[edit]

Throughout R.E.M.'s career, its members sought to highlight social and political issues. According to the Los Angeles Times, R.E.M. was considered to be one of the United States' "most liberal and politically correct rock groups."[114] The band's members were "on the same page" politically, sharing a liberal and progressive outlook.[7]: 155 Mills admitted that there was occasionally dissension between band members on what causes they might support, but acknowledged "Out of respect for the people who disagree, those discussions tend to stay in-house, just because we'd rather not let people know where the divisions lie, so people can't exploit them for their own purposes." An example is that in 1990 Buck noted that Stipe was involved with People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, but the rest of the band were not.[7]: 197

R.E.M. helped raise funds for environmental, feminist and human rights causes, and were involved in campaigns to encourage voter registration.[28] During the Green tour, Stipe spoke on stage to the audiences about a variety of socio-political issues.[7]: 186 Through the late 1980s and 1990s, the band (particularly Stipe) increasingly used its media coverage on national television to mention a variety of causes it felt were important. One example is during the 1991 MTV Video Music Awards, Stipe wore a half-dozen white shirts emblazoned with slogans including "rainforest", "love knows no colors", and "handgun control now".[7]: 195–196

R.E.M. helped raise awareness of Aung San Suu Kyi and human rights violations in Myanmar, when they worked with the Freedom Campaign and the US Campaign for Burma.[115] Stipe himself ran ads for the 1988 election, supporting Democratic presidential candidate and Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis over then-Vice President George H. W. Bush.[116] In 2004, the band participated in the Vote for Change tour that sought to mobilize American voters to support Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry.[117] R.E.M.'s political stance, particularly coming from a wealthy rock band under contract to a label owned by a multinational corporation, received criticism from former Q editor Paul Du Noyer, who criticized the band's "celebrity liberalism", saying, "It's an entirely pain-free form of rebellion that they're adopting. There's no risk involved in it whatsoever, but quite a bit of shoring up of customer loyalty."[7]: 299

From the late 1980s, R.E.M. was involved in the local politics of its hometown of Athens, Georgia.[7]: 192 Buck explained to Sounds in 1987, "Michael always says think local and act local—we have been doing a lot of stuff in our town to try and make it a better place."[118] The band often donated funds to local charities and helped renovate and preserve historic buildings in the town.[7]: 194 [28] R.E.M.'s political clout was credited with the narrow election of Athens mayor Gwen O'Looney twice in the 1990s.[7]: 195 [28] The band is a member of the Canadian charity Artists Against Racism.[119]

Members

[edit]

Main members

[edit]- Bill Berry – drums, percussion, backing vocals (1980–1997, 2024; occasional concert appearances with the band 2003–2007)

- Peter Buck – guitar, mandolin, banjo (1980–2011, 2024)

- Mike Mills – bass, keyboards, backing vocals (1980–2011, 2024)

- Michael Stipe – lead vocals (1980–2011, 2024)

Non-musical members

[edit]- Bertis Downs – attorney (1980–2011), manager (1996–2011)

- Jefferson Holt – manager (1981–1996)

Several publications made by the band, such as album liner notes and fan club mailers, list Downs and Holt alongside the four founding band members[120][38]

Touring and session musicians

[edit]- Buren Fowler – guitar (1986–1987)

- Peter Holsapple – guitar, bass, keyboards (1989–1991)

- Scott McCaughey – guitar, keyboards, backing vocals, occasional bass (1994–2011)

- Nathan December – guitar, percussion (1994–1995)

- Joey Waronker – drums, percussion (1998–2002)

- Barrett Martin – drums, percussion (1998)

- Ken Stringfellow – keyboards, bass, backing vocals, occasional guitar (1998–2005)

- Bill Rieflin – drums, percussion, occasional keyboards and guitar (2003–2011)

Timeline

[edit]

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

- Murmur (1983)

- Reckoning (1984)

- Fables of the Reconstruction (1985)

- Lifes Rich Pageant (1986)

- Document (1987)

- Green (1988)

- Out of Time (1991)

- Automatic for the People (1992)

- Monster (1994)

- New Adventures in Hi-Fi (1996)

- Up (1998)

- Reveal (2001)

- Around the Sun (2004)

- Accelerate (2008)

- Collapse into Now (2011)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Gray, Marcus (1997). It Crawled from the South: An R.E.M. Companion (Rev. ed.). New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80751-0. OCLC 35924957.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Reveal – R.E.M." AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ Harrison, Scoop (June 13, 2024). "R.E.M. Reunite for First Live Performance in 15 Years at Songwriters Hall of Fame". Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ a b Gumprecht, Blake (Winter 1983). "Interview with R.E.M.". Alternative America (Fanzine).

- ^ a b c d Niimi, J (April 28, 2018). "R.E.M.'s first ever show: Opening band at a birthday party in a church". Salon. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ Holdship, Bill (September 1985). "R.E.M.: Rock Reconstruction Getting There". Creem.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg Buckley, David (2002). R.E.M. Fiction: An Alternative Biography. London: Virgin. ISBN 978-1-85227-927-1.

- ^ Phil W. Hudson (April 20, 2016). "Q&A: The Progressive Global Agency President Buck Williams talks Widespread Panic, R.E.M., Chuck Leavell". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ CBS Mornings (June 14, 2024). Extended interview: R.E.M. on songwriting, breaking up and their lifelong friendship. Retrieved June 14, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c Rick Beato (June 14, 2024). Mike Mills: The Story Of R.E.M. Retrieved June 14, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ "'The Father Of Sleep Science' Dr. William Dement Dies At 91". NPR. Event occurs at 1:38. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "R.E.M > Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ^ Nabors, Gary (1993). Remnants: The R.E.M. Collector's Handbook and Price Guide. Eclipse Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-9636241-4-7.

- ^ Denise Sullivan (1994). Talk About the Passion: R.E.M.: An Oral Biography. Underwood-Miller. p. 27. ISBN 0-88733-184-X.

- ^ a b Joe Sasfy (May 10, 1984). "Reckoning with R.E.M." The Washington Post.

- ^ Grabel, Richard (December 11, 1982). "Nightmare Town". NME.

- ^ "Radio Free Europe Archived July 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine". Rolling Stone. December 9, 2004. Retrieved on September 21, 2011.

- ^ Snow, Mat (1984). "American Paradise Regained: R.E.M.'s Reckoning". NME.

- ^ "Interview with R.E.M.". Melody Maker. June 15, 1985.

- ^ Darryl White. "1985 Concert Chronology". R.E.M. Timeline. Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "Artist Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on December 28, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

Stipe, whose on-stage behavior was always slightly strange, entered his most bizarre phase, as he put on weight, dyed his hair bleached blonde, and wore countless layers of clothing.

- ^ Michael Hann (November 15, 2012). "Old music: REM – Feeling Gravity's Pull". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media. Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

I bought tickets for the first of REM's shows at Hammersmith Palais in October 1985... The star, of course, was Michael Stipe. His hair was cropped and dyed blond.

- ^ Robert Dean Lurie (2019). Begin the Begin: R.E.M.'s Early Years. Verse Chorus Press

- ^ Popson, Tom (October 17, 1986). "Onward and Upward and Please Yourself". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Fletcher, Tony (2002). Remarks Remade: The Story of R.E.M. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-9113-2. OCLC 473533197.

- ^ Harold De Muir (July 10, 1987). "There's No Reason It Shouldn't Be A Hit". East Coast Rocker.

- ^ Jon Pareles (September 13, 1987). "R.E.M. conjures dark times on 'Document'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Gill, Andy (March 5, 1991). "The Home Guard". Q. Vol. 55. pp. 56–61.

- ^ Rick Beato (June 14, 2024). Mike Mills: The Story Of R.E.M. Retrieved June 15, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Jon Pareles (February 26, 1992). "Cole's 'Unforgettable' Sweeps the Grammys". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ "Watch "Losing My Religion" Live From MTV's 10th Anniversary Celebration". R.E.M.Hq. November 14, 2014. Archived from the original on May 8, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c Fricke, David (October 3, 1992). "Living Up to Out of Time/Remote Control: Parts I and II". Melody Maker.

- ^ Melis, Matt; Gerber, Justin; Weiss, Dan (November 6, 2017). "Ranking: Every R.E.M. Album from Worst to Best". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ Howe, Sean (November 15, 2016). "After a Trip Back in Time, Michael Stipe Is Ready to Return to Music". The New York Times. p. C6. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ Mojo, November 1996

- ^ Peacock, Tim (September 9, 2019). "New Adventures In Hi-Fi: How R.E.M. Expanded In All Directions". Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ Christopher John Farley (December 16, 1996). "Waiting for the Next Big Thing". Time. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ a b Jim DeRogatis (Fall 1996). "New Adventures in R.E.M." Request. Archived from the original on October 17, 2006. Retrieved December 30, 2006.

- ^ a b Longino, Miriam (October 31, 1997). "R.E.M.: To a different beat the famed Athens band becomes a threesome as drummer Bill Berry leaves to 'sit back and reflect'". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- ^ a b c Black, Johnny (2004). Reveal: The Story of R.E.M. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-776-9. OCLC 440808870.

- ^ "R.E.M. To Score 'Man On The Moon'". VH1. March 1, 1999. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ The Rev. Al Friston (December 2001). "REM: Reveal (Warner Bros.)". rocksbackpages.com. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013.

- ^ Rob Sheffield (May 1, 2001). "R.E.M.: Reveal". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 4, 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- ^ MTV News staff (October 14, 2003). "For The Record: Quick News On Hilary Duff, JC Chasez And Corey Taylor, Mary J. Blige, Deftones, Marilyn Manson & More". MTV. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ^ Dansby, Andrew (October 13, 2003). "Berry Drops In on R.E.M." Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ^ Colin Devenish (September 6, 2002). "R.E.M. Get Primitive". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved December 24, 2007.

- ^ Gary Graff (September 11, 2006). "R.E.M. Bringing Back The Rock On New Album". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved December 24, 2007.

- ^ Jonathan Cohen (September 5, 2006). "R.E.M. Plots One-Off Berry Reunion, New Album". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ^ "It's a Prydz and Stone double top". NME. UK. October 3, 2004. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ Andrew J. Nusca (May 2008). "Bill Rieflin – Steering R.E.M. Into Harder Waters". DRUMMagazine.com. Archived from the original on March 14, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ "R.E.M. inducted into Music Hall of Fame". USA Today. September 17, 2006. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2012.

- ^ Josh Grossberg (March 14, 2007). "R.E.M. Back in the Studio". E! Online. Archived from the original on September 16, 2009. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ Jonathan Cohen (March 12, 2007). "Original R.E.M. Quartet Covers Lennon For Charity". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

- ^ Joal Ryan (October 30, 2006). "R.E.M., Van Halen Headed to Hall?". E! Online. Archived from the original on September 16, 2009. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ Jonathan Cohen (March 13, 2007). "R.E.M., Van Halen Lead Rock Hall's '07 Class". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ^ "REM begin recording new album". NME. UK. May 24, 2007. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved July 3, 2007.

- ^ Jonathan Cohen (August 21, 2007). "R.E.M. Preps First Concert CD/DVD Set". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- ^ Katie Hasty (April 9, 2008). "Strait Speeds Past R.E.M. To Debut At No. 1". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ Paul Sexton (April 7, 2008). "R.E.M. Earns Eighth U.K. No. 1 Album". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ David Fricke (April 3, 2008). "Accelerate review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ William Goodman (November 3, 2010). "R.E.M. Tap Eddie Vedder, Patti Smith for Next Album". Spin. Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ Keith Caulfield (March 16, 2011). "Lupe Fiasco's 'Lasers' Lands at No. 1 on Billboard 200". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Matt Perpetua (July 8, 2011). "R.E.M. Begin Work on New Album". Rolling Stone. Straight Arrow Publishers Company, LP. Archived from the original on September 17, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Robin Hilton (September 21, 2011). "R.E.M. Calls It A Day, Announces Breakup". NPR.org. Archived from the original on September 21, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Matthew Perpetua (September 21, 2011). "R.E.M. Breaks Up After Three Decades". Rolling Stone. Straight Arrow Publishers Company, LP. Archived from the original on September 22, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ David Fricke (September 26, 2011). "Exclusive: Mike Mills on Why R.E.M. Are Calling It Quits". Rolling Stone. Straight Arrow Publishers Company, LP. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- ^ Phil W. Hudson (April 21, 2016). "Q&A: Mike Mills of R.E.M. talks reunion, Georgia, business decisions". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ James C. McKinley Jr. (September 21, 2011). "The End of R.E.M., and They Feel Fine". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 24, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Mike Hogan (November 3, 2011). "R.E.M. Won't Reunite, Michael Stipe Says on U.K. TV". Spin. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ CBS Mornings (June 13, 2024). R.E.M. reflects on band's beginning, breakup and more in rare interview. Retrieved June 13, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Jason Newman (March 17, 2014). "R.E.M. to Release 2 'Unplugged' Concerts for Record Store Day". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media, LLC. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Craig Rosen (November 18, 2014). "Shiny Happy Records: R.E.M.'s Peter Buck Talks 7IN— 83–88 and REMTV Reissues". Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ Melinda Newman (December 15, 2015). "R.E.M. Taps Concord Bicycle to Handle Group's Warner Bros. Catalog: Exclusive". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ Lars Brandle (March 10, 2016). "R.E.M. Signs Global Catalog Deal With Universal Music Publishing Group". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on October 12, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ Marc Schnieder (March 7, 2017). "R.E.M. Signs Performing Rights Deal With SESAC". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ Rietmulder, Michael (March 25, 2020). "Seattle Musician Bill Rieflin of King Crimson, R.E.M. Dies at 59". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Redazione (October 8, 2019). "Michael Stipe: "Il mio album solista? Non abbiate fretta". L'ex R.E.M. risponde a Il Cibicida". Il Cibicida (in Italian). Retrieved September 7, 2024.

- ^ Triscari, Caleb (September 22, 2021). "Michael Stipe confirms R.E.M. will never reunite". NME. Archived from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ Benitez-Eves, Tina (November 14, 2022). "Bryan Adams, Patti Smith, R.E.M., Ann Wilson, Doobie Brothers Among 2023 Songwriters Hall of Fame Nominees". American Songwriter. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ Benitez-Eves, Tina (January 17, 2024). "R.E.M., Steely Dan, and Timbaland Among the 2024 Inductees Into the Songwriters Hall of Fame". Latest News. American Songwriter. ISSN 0896-8993. OCLC 17342741. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ Aswad, Jem (June 14, 2024). "R.E.M.'s Original Lineup Performs Publicly for the First Time in Nearly Three Decades at Songwriters Hall of Fame Ceremony". Variety. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Huhges, William (June 13, 2024). "R.E.M. surprises Songwriters Hall Of Fame crowd with first on-stage reunion in 17 years". The A. V. Club. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Baltin, Steve (April 5, 2020). "10 R.E.M. Great Songs That Aren't 'It's The End Of The World'". Spin. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

But for those first getting into the Georgia-based alt-rock quartet of Michael Stipe, Mike Mills, Peter Buck and Bill Berry (the lineup from 1980 through 1997 until Berry's departure) or those who haven't listened to R.E.M. for some time, here is a guide to 10 of the band's best tracks.

- ^ "R.E.M." Rolling Stone. Wenner Media. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

R.E.M. were a group of arty Athens, Georgia guys who invented college rock

- ^ "Stipe, Carrey Duet On R.E.M." MTV.com. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Reckoning – R.E.M." AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ Graves, Steve. "New Wave Music". St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Retrieved March 30, 2019 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Halbersberg, Elianna (November 30, 1988). "Peter Buck of R.E.M.". East Coast Rocker.

- ^ a b The Notorious Stuart Brothers. "A Date With Peter Buck". Bucketfull of Brains. December 1987.

- ^ CBS Mornings (June 14, 2024). Extended interview: R.E.M. on songwriting, breaking up and their lifelong friendship. Retrieved June 14, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Morthland, John (July 1983). "R.E.M.: Murmur". Creem.

- ^ a b Platt, John (December 1984). "R.E.M.". Bucketfull of Brains.

- ^ a b Olliffe, Michael (January 17, 1995). "R.E.M. in Perth". On the Street.

- ^ Cavanagh, David (October 1994). "Tune in, cheer up, rock out". Q.

- ^ Hann, Michael (January 19, 2018). "I'm a pretty good pop star': Michael Stipe on his favourite REM songs". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon. Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978–1984. Penguin, 2005. ISBN 0-14-303672-6, p. 392

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "American Alternative Rock / Post-Punk". AllMusic. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (2005). "The R.E.M. method and other rites of passage". Spin: 20 Years of Alternative Music (1st ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-307-23662-3. OCLC 60245596.

- ^ Denise Sullivan (1994). Talk About the Passion: R.E.M.: An Oral Biography. Underwood-Miller. p. 169. ISBN 0-88733-184-X.

- ^ Fricke, David (September 26, 2011). "Exclusive: Mike Mills on Why R.E.M. Are Calling It Quits". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ Colin Larkin (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 58. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ David Fricke (October 24, 2011). "'The One I Love': Radiohead's Thom Yorke on the Mystery and Influence of R.E.M." Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ a b c Sommer, Tim (May 29, 2018). "How R.E.M. Changed American Rock Forever". Inside Hook. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ^ Kevin Catchpole (October 30, 2013). "Ed Kowalczyk: The Flood and the Mercy". PopMatters. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ Petrusich, Amanda. "Liz Phair's Songs of Experience". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 19, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2025.

There was R.E.M.—that was a big influence.

- ^ Charles Aaron (October 2005). Notes From The Under Ground. SPIN. p. 122. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (August 1995). "R.E.M. Comes Alive". Spin.

- ^ "Local H on Twitter". Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- ^ Pelley, Rich (February 3, 2022). "Pixies frontman Black Francis: 'Kim Deal? We're always friends – but nothing is for ever'". theguardian.com. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ David Fricke (January 27, 1994). "Kurt Cobain: The Rolling Stone Interview". Rolling Stone.

- ^ "Johnny Marr - There Is A Light That Never Goes Out • 40 Watt Club • Athens, GA • 10/13/18" Archived September 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine - YouTube, published on October 14, 2018

- ^ Gustafson, Hana (September 15, 2023). "The Monkees' Micky Dolenz Announces R.E.M. Covers EP, Shares "Shiny Happy People"". Jambands. Relix Media Group, LLC. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ "Micky Dolenz – Dolenz Sings R.E.M. | Welcome to 7a Records". 7a Records. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (June 21, 1996). "R.E.M.'s Former Manager Denies Allegations of Sex Harassment". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Bands back Burma activist Suu Kyi". BBC Online. September 22, 2004. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- ^ Craig McLean (March 8, 2008). "REM reborn". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ Josh Tyrangiel (October 3, 2004). "Born to Stump". Time. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ^ Wilkinson, Roy (September 12, 1987). "The Secret File of R.E.M.". Sounds.

- ^ "Artists - Artists Against Racism". artistsagainstracism.org. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Cf. (e.g.) the liner notes to Monster

Sources

[edit]- Black, Johnny. Reveal: The Story of R.E.M. Backbeat, 2004. ISBN 0-87930-776-5

- Buckley, David. R.E.M.: Fiction: An Alternative Biography. Virgin, 2002. ISBN 978-1-85227-927-1

- Gray, Marcus. It Crawled from the South: An R.E.M. Companion. Da Capo, 1997. Second edition. ISBN 0-306-80751-3

- Fletcher, Tony. Remarks Remade: The Story of R.E.M. Omnibus, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7119-9113-2.

- Platt, John (editor). The R.E.M. Companion: Two Decades of Commentary. Schirmer, 1998. ISBN 0-02-864935-4

- Sullivan, Denise. Talk About the Passion: R.E.M.: An Oral Biography. Underwood-Miller, 1994. ISBN 0-88733-184-X

External links

[edit]- Official website

- R.E.M. on the Internet Archive

- R.E.M. at AllMusic

- R.E.M. discography at Discogs

- R.E.M. discography at MusicBrainz

- R.E.M. at IMDb

- Dynamic Range DB entry for R.E.M.

- R.E.M.

- 1980 establishments in Georgia (U.S. state)

- 2011 disestablishments in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Alternative rock groups from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Brit Award winners

- Capitol Records artists

- Concord Bicycle Music artists

- Grammy Award winners

- I.R.S. Records artists

- American folk rock groups

- Jangle pop groups

- Musical groups established in 1980

- Musical groups disestablished in 2011

- Musical groups from Athens, Georgia

- New West Records artists

- Rhino Entertainment artists

- Warner Records artists

- Craft Recordings artists

- College rock musical groups

- American post-punk music groups

- Musical quartets from Georgia (U.S. state)